Towards a general theory of evolution

Neo-Darwinism seems to be overcome, and there is already a need for a paradigm shift which reformulates and completes the Theory of Evolution.

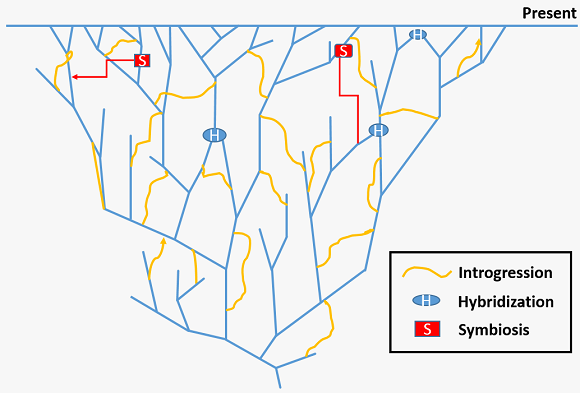

A recent comment by Elizabeth Pennisi (Science, 18 November 2016) refers many examples of the omnipresence of hybridization between species, not only in prokaryotic microbes and in plants but also in animals, humans included (we know that our genome contains genes coming from Neanderthals and Denisovians). Pennisi considers that this challenges evolutionary theory. The Mayr’s concept of biological species (in which the reproductive isolation is a necessary condition to recognize for a group of individuals the category of species) is staggering: many species hybridize with relatives producing fertile descendants, and the tree of life becomes a network.

I agree. In Noticias sobre evolución (2015) I exposed the current difficulties of the neo-Darwinian paradigm. In the prokaryotes there is a lot of genetic promiscuity and there are more or less frequent (but in no case very rare) hybridization evidences in all main large groups of organisms, and we have to add introgressions mediated by viruses, microbes or or other parasitic or symbiotic organisms. My feeling is that we approach a paradigm change, the type of crisis described in 1962 by Thomas S. Kuhn in The Structure of scientific revolutions. I can not debate epistemological problems here, but I recall that, even if the paradigms must be defended, frequently, when they are like castles in ruins occupied by scientists who have been the pontiffs of a particular branch of science, the old paradigms become obstacles to knowledge progress.

In another article in this blog I have referred to the difficulties hindered by innovative researchers, as Barbara McClintock or Lynn Margulis (two women, and this is perhaps not casual), to see their ideas generally accepted. But it is also true that Kunt warned that “a paradigm can not fall if there is not a new one to replace it, because this would be to reject the science itself” and, whereas some attempts have been made to build an alternative paradigm to the neodarwinism (see Jablonka & Lamb Evolution in four dimensions), the work is far from finished. Next years, the use of CRISPRs and other techniques that allow to explore genomes in a fast and cheap way, and also to manipulate them easily, will permit a great knowledge increase. Meanwhile, the priests claiming against heretics rear the partially ruined walls might better come to the open field and consider if it is the time to widen the frame: we will continue to be darwinists (and not post-darwinists), but what by 1940 was neo- now is becoming paleo-.

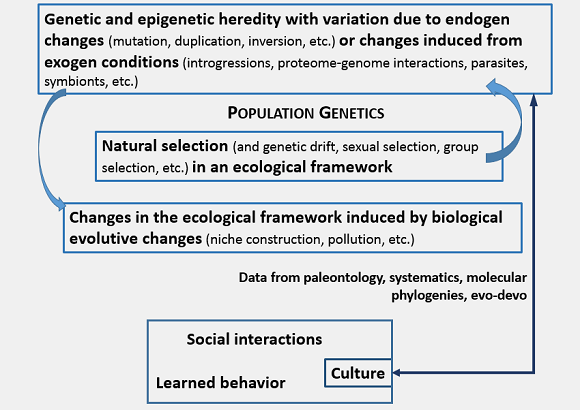

The neodarwinism (to follow Einstein’s terms) is like a special theory of evolution. It integrated the Darwin's natural selection theory, the Mendelian theory of inheritance —with mutation as the source of variation— and the statistics approach of population genetics. The new general theory of evolution might relate natural selection (and genetic drift, sexual selection, group selection, etc.) with heredity (with endogenous and exogenous genetic variation), learned heredity of behavior between generations, a solid evo-devo theory, phylogenetic reconstructions on the basis of molecular techniques, population genetics and the consideration of an ecological framework that not only filters changes but also induces more or less fast change rates, and that is in part built during the evolutionary process.

Furthermore, the general theory of evolution might include culture as an evolutionary product in a number of species. Perhaps we could use a word like dictiodarwinism, from the Greek δίκτυο that means ‘network’, because the genome-epigenome, the proteome, the social groups, the ecosystems, the languagues, etc... all work as networks). But more than a name, the general theory requires a mathematical formulation similar to what Fischer-Haldane and Sewall Wright made for neodarwinism. It is not easy.

Finally, the mechanisms of cultural evolution are not based on reproduction and heredity with variation and selection, but in imitation, plagiarism, learning, use and modifications of languages and tools... and the choice of what endures depends not only on fitness but on economic and social relations of power, on history and random. Furthermore, the evolution has produced culture and culture in turn influences biological evolution. Even, as in domestication and genetic engineering, culture can drives biological evolution and, in fact, will do this more and more. And here there is not just darwinism but not necessarily well intentioned intelligent design, and perhaps not as intelligent as it could be wished.