ChatGPT underestimates the urgency entailed by climate change in plant science

A new study published in the journal Trends in Plant Science shows that ChatGPT can help to generate scientific questions related to plants, albeit with limitations. The study also finds that, in the field of plant science, ChatGPT overlooks the importance of aspects such as the urgency that climate change entails, political context, the most recent research, and the need for multidisciplinary work. In the light of the study’s findings, its authors point out that any list of ChatGPT-generated questions should be enriched with a human perspective. “We have detected a bias towards the most abundant content, so basing our work on this technology would risk narrowing our scientific outlook,” explains CREAF-based CSIC researcher Josep Peñuelas, one of the aforementioned authors. That bias is illustrated by ChatGPT identifying the use of plants to develop sustainable products as the number one priority of research in plant science, something Peñuelas attributes to the vast amount of internet content in which plants are associated with plant protection products, medicines, clothing, etc.

“We have detected a bias towards the most abundant content, so basing our work on this technology would risk narrowing our scientific outlook.”

JOSEP PEÑUELAS, CREAF-based CSIC researcher and co-author of the study.

A hundred priorities

In comparison to the scientific community, ChatGPT does not attach great importance to climate change or carbon capture.

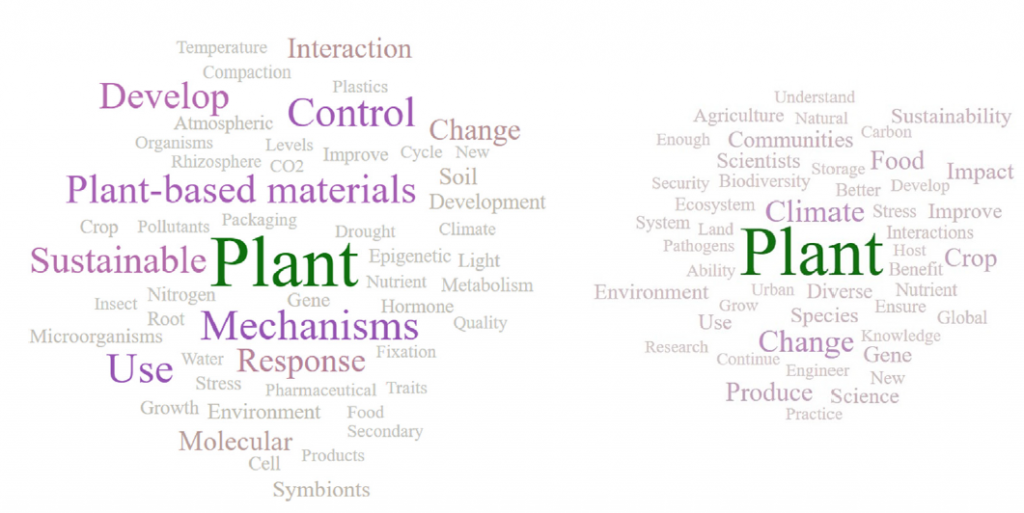

To carry out their research, the authors asked ChatGPT to produce a hundred important questions on which plant science ought to focus in the coming years. They then contrasted its response with a hundred such questions that an international scientific study conducted previously had already established. “Our aim was to assess the differences and find out how similar the results were,” says Peñuelas. When they compared the two lists of questions, the researchers saw that both included aspects such as plant-pollinator interactions, nitrogen fixation, and the use of plants to develop sustainable products. However, ChatGPT’s list largely omitted certain matters the researchers deem extremely relevant, among them topics related to climate change and carbon capture, which Peñuelas describes as “high on the social and political agenda.” Furthermore, it overlooked cutting-edge areas of plant science, such as priming (i.e. the study of plants’ immune systems), which could aid the development of ‘plant vaccines’ against pathogens, insects and other stressors, and investigating seaweed’s potential for reducing pollution. That, as Penuelas notes, is probably because little information on the matters in question has yet been published.

Additionally, the study’s authors asked ChatGPT to come up with the ten most important questions plant science will need to address in the second half of the 21st century, and then to do likewise for the 22nd century. The responses generated differed in each case. “That shows ChatGPT is capable of giving different answers according to the scenario,” remarks Peñuelas.

Alongside CREAF, the institutions participating in the research were the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Nanjing University, Freie Universität Berlin, and the Berlin-Brandenburg Institute of Advanced Biodiversity Research (BBIB). The authors of the study conclude that ChatGPT can speed up bibliographic review and analysis processes, but warn that it should be used with great caution and always with the perspective of the scientific community.

The limitations of basing science on artificial intelligence

ChatGPT does not take into account questions that require a deeper understanding of the world.

The results of the study also show that ChatGPT does not take into account questions that require a deeper understanding of the world and are crucial to the progress of science. It does not mention, for example, that it is important to transfer scientific results to policy-making, to strengthen the connection between science and society, or to maintain the genetic biodiversity of plants, which is essential in a situation of climate and biodiversity crisis; nor does it mention the importance of science working with other disciplines, such as architecture and engineering to make cities greener, or farming to tackle the issue of food security. “Such subtleties are beyond it at the moment,” explains Peñuelas.

Referenced article

Agathokleous, E., Rillig, M.C., Peñuelas, J., Yu, Z. 2023. One hundred important questions facing plant science derived using a large language model. Trends in Plant Science https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2023.06.008