CREAF researchers study climate change-induced permafrost melt in Arctic peat bogs in Alaska

The main carbon store in the planet’s soil is peat, a deposit of plant origin found in water-saturated areas called peat bogs or peatlands. In total, peatlands contain over 550 gigatons of carbon in the form of partially decomposed plant matter, representing 42% of all soil carbon worldwide.

There are peat bogs everywhere from the tropics to the polar icecaps, but polar peatlands are particularly important because of the large expanse of the Earth’s surface they cover and the fact that they often lie in areas of permafrost, i.e. perennially frozen ground. Permafrost immobilizes carbon in peat, helping prevent it from being released into the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) or methane (CH4). There is permafrost under approximately 25% of the surface of the Northern Hemisphere.

Permafrost immobilizes carbon in peat, helping prevent it from being released into the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide or methane.

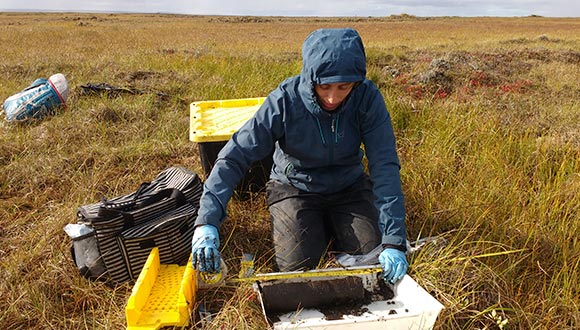

CREAF researchers Olga Margalef, Oriol Grau and Sergi Pla-Rabés have recently returned from an expedition to northern Alaska (Toolik, 68º N), which they undertook to gain an insight into what will happen if global warming causes the permafrost in peat bogs to melt. Understanding the key role peatlands play in the functioning of the planet is vital and urgent, not only because they act as a carbon sink but also because they contain a large quantity of essential nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, whose cycle in such ecosystems has been the subject of very little study.

“Permafrost degradation is occurring because rising temperatures are melting the ice it contains”, says Olga Margalef. “Southern permafrost boundaries are receding northwards and have fallen back by 30 to 80 km over the last few decades”, she notes. “It’s crucial that we study the effects of the thawing of permafrost to understand how biogeochemical cycles could change worldwide”, she continues. “We expect that huge amounts of CO2 will be emitted into the atmosphere, and that large quantities of phosphorus and nitrogen will be released into water and made available to organisms.”

Southern permafrost boundaries are receding northwards and have fallen back by 30 to 80 km over the last few decades.

This was the researchers’ second field campaign, following a previous expedition to the province of Lappland in Sweden. Both campaigns received funding from INTERACT (a European initiative for giving young researchers access to remote research stations) through the P-PEAT and P-PEAT 2 projects.

The samples taken in Sweden shed light on 9,000 years of the region’s history

In 2018, the researchers sampled plants and soil at a range of depths in Sweden, where the permafrost is discontinuous and the ice forms small, lentil-like spots. Their goal was to compare areas in which the permafrost had remained intact and others in which it had recently thawed. “Frozen soil isn’t easy to sample – it’s as hard as rock – and you have to use a drilling machine”, remarks Oriol Grau. “The one we used was designed specifically for our work and was fitted with a motor”, he explains.

The goal was to compare areas in which the permafrost had remained intact and others in which it had recently thawed.

The researchers also took a continuous sample of soil spanning a vertical distance of more than a metre to enable them to study the layers of peat that had been built up over time and which the permafrost had preserved like the pages of a book. The sample will be used to reconstruct environmental conditions in the distant past. “The sample contains more than 9,000 years of the region’s history, so it will help us understand the dynamics of permafrost formation and degradation in the Holocene”, says Sergi Pla-Rabés.

Alaska’s permafrost is melting too

In Alaska, in contrast, the permafrost is continuous. Even so, the researchers observed permafrost zones where warming had already caused degradation, both at the edges and in the middle of peat bogs. They did so by taking peat samples at different depths in the unfrozen, living surface layer and the frozen part alike. They also sampled plants and carried out exhaustive sampling on water to study its chemistry and the abundance of diatoms (a type of microscopic algae) in it.

The researchers reported that colder temperatures, heavy rain and snow, and a two-and-a-half-hour slog from the research station to the sampling area made the second campaign a great deal harder than the first.

"The researchers observed permafrost zones where warming had already caused degradation, both at the edges and in the middle of peat bogs."

Comparing the findings of the two campaigns will help further our understanding of the effects of the thawing of continuous and discontinuous permafrost.