Endemic animals and plants are unique to each region

Just as Michelangelo only painted one Sistine Chapel and located it in the Vatican, nature has promoted unique, special species of flora and fauna that only live in one place in the whole world. These are known as endemisms and the Montseny newt, the lizard of the Pitiüses, or the Séseli of the Cap de Creus are examples that we work with at CREAF. We speak of an endemic species when all the members of this species of animal, plant, or fungus live in a single place in an entire region. And in this case, scale plays an important role: we can speak of Catalan endemisms with respect to the rest of the peninsula or of an Empordà endemism with respect to the whole of the Catalan territory. In fact, some widely distributed species are actually endemic if we analyze them in comparison with the whole of Europe, as is the case of the well-known Iberian lynx, a peninsular endemic species.

Endemic species are at risk from global change, because the climate, soils and environment of these fauna and flora are changing too rapidly for them to continue to adapt and evolve in line with their region.

Endemic species are at the same time very interesting in evolution, as some of them appeared millions of years ago (the paleoendemisms) and have adapted to the ecosystem in which they live. In the current context of climate change this is a problem, because the climate, soils and environment of these fauna and flora is changing too fast for them to continue adapting to it and evolving hand in hand with their region. "If we lose an endemic species, we lose a whole genetic line and we also lose its evolutionary strategy, which has made it adapt so well to a particular environment. This is very useful for researchers, because it helps us to study where future innovations in nature may come from in order to adapt to global change. Moreover, in many cases an endemic species is key to its habitat, and if it disappears, the whole ecosystem may disappear. Everything is linked. Imagine the disappearance of a rodent that disperses the seeds of a specific tree in the forest. The reproduction of the tree will be affected and in the long run its viability will also be affected because if the rodent species is endemic it cannot be replaced," says CREAF researcher Sandra Nogué.

If we lose an endemic species we lose a whole genetic line and we also lose its evolutionary strategy, which has made it adapt so well. This is very useful for us to study where nature's future innovations to adapt to global change may come from

SANDRA NOGUÉ, CREAF researcher

Islands, the "great factory" of endemisms

Although islands lack a large number of species compared to mainland areas, they are a hotspot for endemic species. When an island emerges, the species that arrive occupy all the habitats where they can fit in, and over time they adapt and transform themselves to live exclusively there (they cannot escape!). In addition, it is interesting that some islands have very special characteristics and, therefore, also the endemic fauna and flora living there is very different from the rest of the world. Without going any further, the Teide peak on Tenerife with an altitude of around 3,700 km is like a museum of relicts because species survive that have already become extinct at lower altitudes and on the rest of the continent thousands of years ago!

The distinctive features of island species will vary depending on whether the species appeared when the island was formed (neoendemic) or whether they were already living on the nearest continent, but due to past environmental changes became extinct and remained only on the islands (palaeoendemic), as is the case of the Teide or the Canary laurel forest mentioned above. "Oceanic islands and large tropical islands make an important contribution to global biodiversity, because they act as bridges between land masses and are an important point of formation of neoendemic species. Ecologically this phenomenon is known as explosive radiation and we can find it for example in the Galapagos and Borneo," explains Nogué.

Endemic species are generally already highly vulnerable to change, but on islands this is even more pronounced, as the distribution is even narrower and the closest populations are separated by seas and oceans.

While endemic species are already highly vulnerable to change in general, this is accentuated on islands, where the distribution is even narrower and the closest populations are separated by seas and oceans. On islands, the probability of extinction increases exponentially and hence the restrictive policies on the transport of plants and animals in some island countries such as Australia and New Zealand. To illustrate this, the case of the South Atlantic island of San Giorgia is well known. In the 18th century, several whalers came to the island to hunt and introduced rats and plants (e.g. Poa annua). The rats ate the eggs and chicks of the island's endemic birds and their populations began to decline severely, to the point that by the 2000s almost 99% of native birds had been lost. After intensive eradication campaigns and many years of monitoring, in 2018 Sant Giorgia del Sud was declared the first rat-free territory in the world.

Endemic species close to home

Catalonia is a land of endemic species. In the same way that we can find various microclimates and species which have gradually adapted, there are many unique species which are as unique as a work of Michelangelo. CREAF has studied several of them in recent years, such as the Ramonda myconi plant (which is distributed throughout the north of the peninsula), the Montseny newt, the Cape Creus sesseli or even the Syrian flora Iris nusairiensis. We discover them for you.

The Pitiüses lizard

The Podarcis pityusensis is a lizard endemic to the Pitiüses islands (Ibiza, Formentera and the islets around these two islands). It is a reptile that inhabits the dry stone walls so typical of the Mediterranean, abundant in these locations, but highly threatened by some invasive species that have reached the islands, such as the horseshoe snake, and by extreme weather phenomena. This snake has reached Ibiza through the importation of olive trees for gardening.

Oriol Lapiedra, a CREAF researcher who studies the behaviour of this species, explains that "the Pitiüses lizard forms an important part of the culture of these islands, they are an important part of the landscape of these islands and there is even a lot of merchandising around them. I personally think that this connection between culture and biodiversity is important because it connects people with nature in a Mediterranean environment that is particularly threatened by development and habitat destruction. Also, this species is what we know as a "keystone species", a keystone species for the ecosystem. If this keystone species is lost, the biological system of which it is a part changes substantially and may even collapse. In its case, for example, it feeds on insects that can become a pest.

“This connection between culture and biodiversity is important because it connects people with nature in a Mediterranean environment particularly threatened by development and habitat destruction”

ORIOL LAPIEDRA, CREAF researcher.

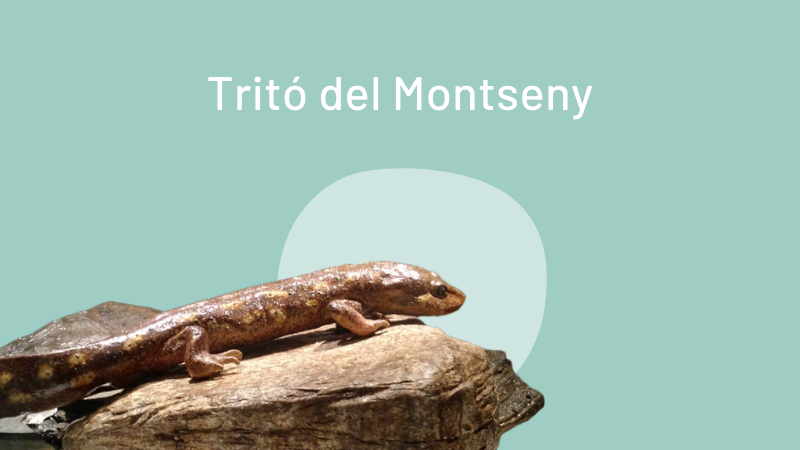

Montseny’s newt

The Montseny newt is a species of amphibian that only inhabits the small streams of the highest parts of the massif that gives it its name (an area of less than 25 km2). For this reason, it is currently classified as a species in serious danger of extinction by the IUCN. It is practically aquatic, found in the cold, clean and oxygenated waters of the streams in the beech and holm oak forests where it breeds and feeds. Although their biology is still largely unknown, studies indicate that they move very little. This low dispersal capacity and the existence of few suitable streams for the species could eventually lead to the loss of individuals and, in the long term, could lead to their extinction.

"The increase in forest in the Montseny may mean that the streams where the newts live do not carry enough water for long periods of time, and this could jeopardise the project to reintroduce the species that is being carried out in Catalonia. "If the forest grows, the trees need more water, and the flow of the streams decreases. In fact, this effect is the main threat to the species, more than the increase in temperature or the lack of rainfall that climate change is already causing", reveals a study by Anna Ávila, CREAF researcher.

“If the forest grows, the trees need more water and stream flow decreases. In fact, this effect is the main threat to the species, more than the increase in temperature or the lack of rainfall that climate change is already causing”.

ANNA ÀVILA, CREAF researcher.

Cap de Creus’ sèseli

Seseli farrenyi is an endemic plant of the Cap de Creus Natural Park. It grows in the shape of an umbel, with white flowers of approximately 20 × 20 cm and between rocks and cliffs. "This species is important because in addition to being unique in the world, it is only found in a very small town on the Cap de Creus and that makes it very vulnerable. If we want to stop the loss of biodiversity, we must avoid the extinction of all species, not just those that give a direct benefit to humans, "says Sandra Saura Mas, CREAF researcher and UAB professor who has been more than 13 years studying and participating in its recovery.

“If we want to stop the loss of biodiversity, we must avoid the extinction of all species, not just those that give a direct benefit to humans.”

SANDRA SAURA MAS, CREAF researcher

Recently, new localities of this plant were found, after 10 years of witnessing its decline and path to extinction. Now the population has quadrupled and the biologist is hopeful for the conservation of the species.

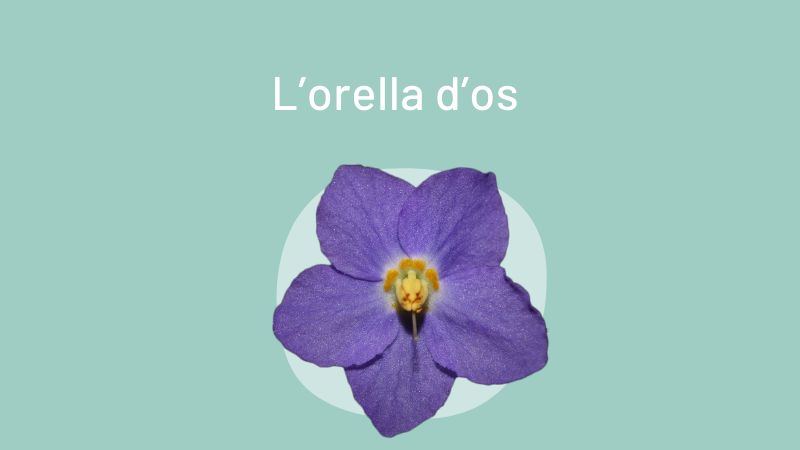

Ramonda myconi

Also known as hairy grass, the Ramonda myconi is a species that has lived in the Pyrenees for millions of years. It began to live there when it still had tropical characteristics during the Tertiary period and has adapted to environmental changes over time until the present day, where it is well adapted and at minimal risk of extinction.

This plant with violet flowers, which can reach 20 cm in height and which sprouts again year after year, although it seems to dry up every summer in the heat, was studied by our researcher Maria Mayol and our researcher Miquel Riba . In addition to Catalonia, it can be found in Navarre, Aragon, France and Andorra among calcareous rocks and conglomerates.

Beyond Catalonia

In addition to the most endemic species, CREAF is involved in the search for other species that are unique throughout the world. One of these is the Iris nusairiensis, to which Angham Daiyoub, a PhD student at CREAF and the UAB, is devoting her thesis. This species of iris lives only in the coastal mountains of Syria, between 1,000 and 1,600 metres above sea level.

It is a plant with bluish or white flowers that grows in bulbs with long fleshy storage roots. It usually has about 6 glossy, medium green, lanceolate leaves that rise from the base of the stem and can reach 7-10 cm in height in males. All flowers have a yellow or pale yellow crest on the cascades. "Right now we are studying it to find out more about its biology, as it is classified as a species of special concern by the IUCN in the Mediterranean and is vulnerable because of its very restricted distribution," explains Daiyoub.