New forests grow faster but are more sensitive to climate change

A study led by CREAF has found that new forests growing on abandoned rural land are able to capture more carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere than long-established forests. This effect could be temporary, however, as the wood of their trees is less dense, making them more vulnerable to extreme climate events.

A lot of farmland was abandoned in the rural exodus of the 20th century, particularly in Mediterranean Europe. Trees have gradually grown on that land, forming what are referred to as “new forests”. What is the role of such forests and can they help us combat climate change?

Led by CREAF researchers Raquel Alfaro-Sánchez and Josep Maria Espelta, a recent study published in the journal Agricultural and Forest Meteorology shows that new forests of the kind described grow 32% faster than more established forests, even when tree age and density are factored in. That is good news, as trees with a higher growth rate capture more CO2 from the atmosphere and could thus help mitigate its greenhouse effect. According to the study, one of the reasons for which new forests grow so quickly is that the land on which they stand is highly fertile owing to the farming activities for which it was previously used.

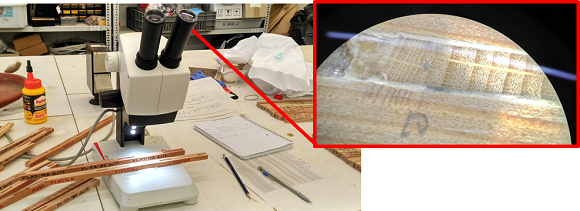

The researchers who conducted the study extracted wood cores from trees in recently established (post-1956) and long-established (pre-1956) beech forests in Osona and Ripollès in Catalonia. They established each tree’s growth rate by examining its rings (the wider its rings, the higher its growth rate).

Faster growth can mean greater vulnerability to climate change

The researchers also identified a downside to faster growth, one that is especially relevant in today’s changing climate. Their results clearly showed the trees’ wood density to be 3% lower due to their high growth rate. “Lower wood density makes trees less able to cope with extreme weather conditions, such as drought, or other events, such as infestations or strong winds”, says Raquel Alfaro.

“At the moment, the new beech forests are responding very well in years when there is plenty of rainfall, and that’s helping them deal better with worse conditions in years of drought”, remarks Josep Maria Espelta, CREAF’s coordinator for the project. “But that effect could tail off or even disappear if droughts become more frequent, as they’re very likely to in the future”, he continues. Should that be the case, the ecosystem services new forests provide will not last very long. With that in mind, forest management will need to take the possible differences the study has identified between recently established and long-established forests into account so as to guarantee their survival against the backdrop of the present environmental crisis.

The study was carried out as part of the EU-funded SPONFOREST project, with the participation of researchers from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the University of Stirling.

Referenced article:

Alfaro-Sánchez, R., Jump, A. S., Pino, J., Díez-Nogales, O., & Espelta, J. M. (2019). Land use legacies drive higher growth, lower wood density and enhanced climatic sensitivity in recently established forests. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 276, 107630.