The Roots of Heaven: Literature and Ecology

Environmentalsim and literature in a book, then filmed for the big screen, by Romain Gary.

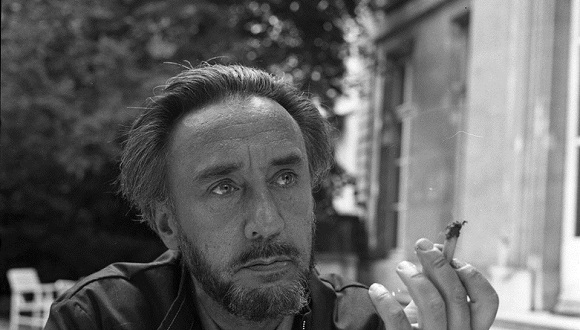

When summer holidays approach, I would like to recommend a novel: The Roots of Heaven by Romain Gary, a Russian Jew born in Lithuania who became one of the best-known 20th century’s French writers, a film director and a screenwriter. His life was like a novel. He won two prizes Goncourt, the only author who has done so, the second of them using the alias Émile Ajar to make fun the critics who said of him that he was an antiquated romantic and who, instead, glorified the "young innovator" Ajar, ignoring that he was Gary until after his death.

He married to the American actress Jean Seberg, whom he could not save from her ghosts. They had a son who wrote the story of his parents and who owned the bookshop Lletraferit, at the Barcelona’s Raval. Seberg committed suicide with alcohol and barbiturates in 1979. Gary did the same 16 months after by a shot in the mouth, leaving a note in which he unlinked his act of Seberg’s death and having previously emancipated his 16-year-old son and left him his goods.

The Roots of Heaven was published in 1956 and won Gary's first Goncourt. It is an ’ecological’ novel with remarkable characters. John Huston directed a forgotten film adaptation with Trevor Howard, Errol Flynn, Orson Welles and Juliette Gréco. The motor of the story is a man named Morel who undertakes a crusade in Chad (French colony at the time of the book), in defense of African fauna and flora, and especially of elephants. Taken by a crazy misanthropist, he accepts the company of an ambitious black politician, Waïtari, educated in France, who wants the independence of Africa (but want to become a dictator) and hopes to use the riots originated by Morel —that conduces several attacks without deaths against hunters and ivory traders— to announce an inexistent insurrection. Morel does not like politics, he only agrees with those who intend, like him, to save the elephants, no matter how they think or from what country they are. He believes that the man needs friends "bigger than the dogs".

The various interpretations of Morel's true motivations give rise to interesting comments (somewhat repetitive) about whether progress in Africa can afford the burden of elephants and wildlife. Some consider necessary to remove the population from misery and magical traditions by using all the space whereas others see landscape changes as a loss for freedom. One of them claim "where there are elephants, there is freedom". "The human species has come into conflict with the space, the land and even the air it needs to live. The cultivated lands will gradually gain ground on the forests and the roads will invade more and more the calm of the great herds," says another.

Is Morel a fool? It seems to be. Another character says: "Poor Morel, he has got himself into a dead end. No one has ever been able to solve the contradiction that exists in defending a human ideal in the company of men." But Morel appears more and more to be convinced that saving the elephants is an act of humanity: it is necessary to feed the blacks so that they do not have to kill the elephants: "both things go together, it is a matter of dignity", he states. Waïtari, on the other hand, believes that the Morel’s vision of the elephants "nobility and beauty" is only decadent bourgeois sentimentalism. Morel's media success bothers him because it hides the supposed anti-colonial insurgency (and Waïtari’s own role). Wild nature is, for him, a burden to be left back and Morel might be killed before he become arrested and he can deny any political motivation.

The various interpretations of Morel's true motivations give rise to interesting comments about whether progress in Africa can afford the burden of elephants and wildlife. Some consider necessary to remove the population from misery and magical traditions by using all the space whereas others see landscape changes as a loss for freedom.

Another character says about Morel: "This guy suffers from a too noble idea of man... Such a request never forgives. You cannot live with this... We do not have what is necessary..." But Morel's faith in humans always resists, although he is aware of the inadequacies of our nature, the enormous weight that fate (our characteristics as a species) places on our back. He hopes that science will help, for example by inventing "pills of humanity". And he believes that we must continue to fight: as the first fish that came out of the mud without having lungs yet, we must try it even if our nature does not help, because maybe someday, he says, we will have an "dignity’s organ." This commitment to the future of an improved humanity makes us now think of post-humans, that we consider always between some hope and with the fear of a new deception about ourselves.

The book is full of disenchanted human beings, who have endured one or two world wars and have reached a dump of the world led by the storm. In them, Morel provokes the most opposing reactions. Some, however, sympathize with the idea that Morel’s struggle for elephants is, also, a struggle for human dignity, even though many see this as a no hope aim. But Morel learned in the Nazi concentration camp that an apparently useless gesture of rebellion can reach the hearts of other people. Humans respond more by intuition and empathy than by reasoning. Giving an example is, then, effective.

From the point of view of environmentalism, the book raises basic questions that today are still well in force, with a surprising degree of penetration for the time. Is there room for the large African herds in the world we are doing, or will their destiny be that of bison in North America? If we are we already witnessing the death of the Great Australian Barrier, the sixth great extinction and the climate change, what does all this say about us?

Some, however, sympathize with the idea that Morel’s struggle for elephants is, also, a struggle for human dignity, even though many see this as a no hope aim.

Today, there are two different trends among conservationists: a) those who preach a reformist ecology, who wants to introduce even monetary valuations of ecosystem services to help a more careful decision-making about the environment and open new avenues of business in a more sustainable world; and b) what is called deep ecology, which raises the issue from an ethical point of view, recognizing the inherent value of species and the biosphere (I hope to discuss in another post the controversial aspects of deep ecology). Morel is closer to this second position because "saving the elephants" is to strengthen our own dignity against a system that assaults life. And, as he says, we all have "elephants" to save.

A book that we should recover... If someone is encouraged, I will appreciate comments.