220 lizards show there to be reciprocal feedback between ecology and evolution

Finches were vital to the formulation of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. The size and shape of their beaks, highly suited to eating different types of seeds, helped him understand how an animal evolves to adapt to the ecological conditions of its ecosystem. The Galapagos Islands were an ideal laboratory for Darwin, but there was something he overlooked: was it only the finches that had evolved or had the seeds of the plants they fed on evolved a little too?

It is not only the case that ecological changes lead to evolution, but also that evolutionary changes prompt changes in ecosystems.

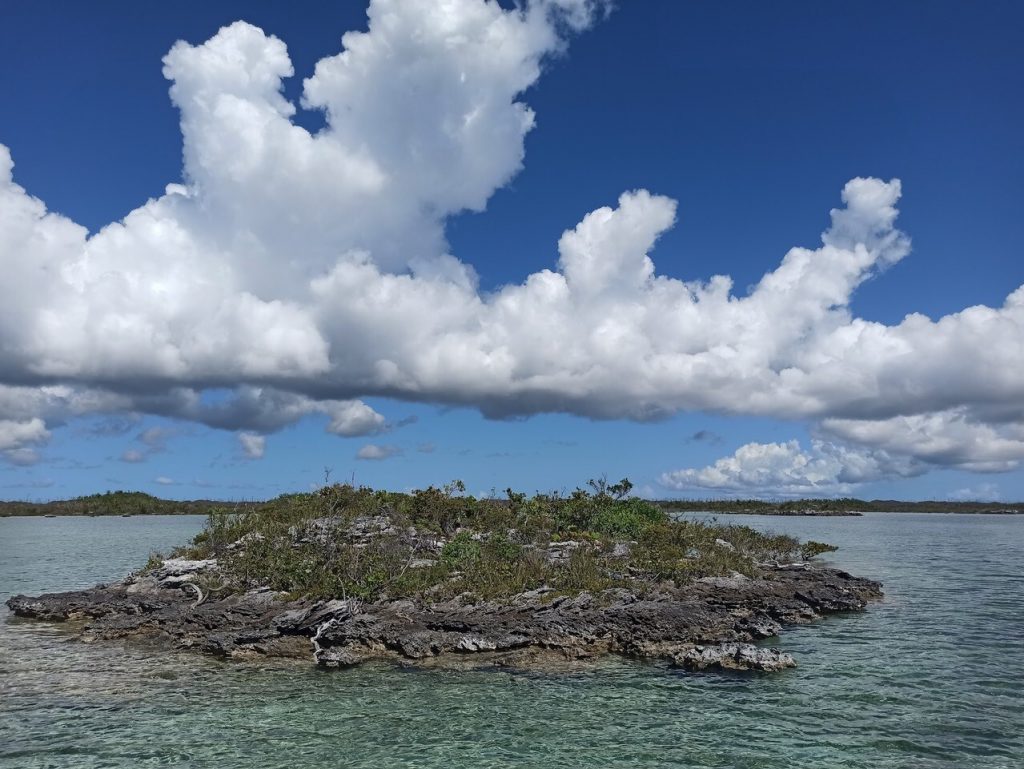

CREAF researcher Oriol Lapiedra has today published an article in the journal PNAS. It reveals an inextricable link between ecology and evolution, in that it is not only the case that ecological changes lead to evolution, but also that evolutionary changes prompt changes in ecosystems. The study described in the article provides evidence that ecology and evolution can be two sides of the same coin and that nature adapts and evolves more swiftly than Darwin suspected. To obtain that evidence, an international research team conducted an experiment on 16 small islands, using 220 brown anole lizards(Anolis sagrei), a species typical of the Bahamas. They found that vegetation, arthropod populations, and interactions throughout an island ecosystem can change in response to the arboreal reptiles’ limb length in just eight months.

In the surprising experiment, brown anole lizards with short limbs proved to be better at climbing up trees and to catch more herbivorous insects and spiders. That resulted in faster growth of buttonwood(Conocarpus erectus ) shrubs on the islands with shorter-legged specimens.. Previous studies have already shown that if long-limbed lizards arrive at a small island, their descendants quickly evolve to have shorter limbs.

“Per una banda, com que els llangardaixos que es mouen millor entre aquests arbustos són els de cames més curtes, s’afavoreix als llangardaixos de cames més curtes en una relació que es retroalimenta, aquesta part demostra l’efecte de l’evolució sobre l’ecologia. D’altra banda, la selecció natural afavoreix els animals que es mouen millor en les branques primes dels arbustos d’aquestes illes, els de potes més curtes, el que demostra l’efecte de l’ecologia sobre l’evolució”.

ORIOL LAPIEDRA, investigador del CREAF i un dels autors d'aquest estudi.

220 lizards on 16 islands

To carry out the study, the researchers captured and measured 488 brown anoles, lizards that feed on spiders and insects. They kept the specimens with the shortest legs and those with the longest legs, and took them to 16 small Caribbean islands whose entire lizard populations had been wiped out by Hurricane Dorian. They left the 110 lizards with the shortest legs on eight of the islands and the 110 with the longest legs on the other eight islands, and returned eight months later.

The results were clear. On the islands where the short-limbed lizards had been left, the spider population had fallen by 41% and the most common vegetation had grown at a rate of 102%. In contrast, on the islands where the long-limbed brown anoles had been left, their presence did not appear to have had any significant effect on vegetation growth.

Referenced article

Kolbe, J. J., Giery, S. T., Lapiedra, O., Lyberger, K. P., Pita-Aquino, J. N., Moniz, H. A., Leal, M., Spiller, D. A., Losos, J. B., Schoener, T. W., & Piovia-Scott, J. (2023). Experimentally simulating the evolution-to-ecology connection: Divergent predator morphologies alter natural food webs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(24). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.222169112