A feather for the hat, ma'am?

Birds for their feathers, but many other animals too, suffer the path to extinction because of human whims.

John James Audubon (1785-1851) was an ornithologist born in France and nationalized American, author of highly valued paintings that represent birds and of the book Birds of America. He has given his name to the National Audubon Society, dedicated to the conservation of birds and their habitats, one of the oldest conservation entities in the world. However, Audubon, very interested in the study of birds, was not a conservationist. He killed birds to draw them (he used a wire to make the corpses stay in a natural position) and he did it in large numbers. He considered a site poor in birds the day he killed less than a hundred. If the bird was uncommon, he chased it harder. It should be said, as an excuse, that, in his time, nobody cared too much about conservation.

The use of feathers as an ornament is very old. Even it pre-dates our species, because the Neanderthals already practiced it. We find it in very diverse cultures and we all remember the spectacular arrangements of the tribe’s chiefs of North-american Indians that we have seen in the movies. The feathers of ostrich, birds of paradise, peacock, marabou, heron, vulture or rooster have been traded worldwide. Some types of feathers have been very valuable and, therefore, a cause of great bird’s massacres, although they were also hunted for sale to museums. In order not to spoil the material, the hunters used small bullets.

A good place to hunt birds and take their feathers in the late 19th century was in the Florida Everglades. Some ardeids have, in the breeding season, long filamentous feathers. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, some of these species were object of an insistent persecution by the demand of their beautiful white feathers to decorate hats and other uses. This promoted the emergence of conservationist movements that contributed to the enactment of the first laws on bird’s conservation.

This whole group of species lives in wetlands, both fresh and salt water. The cattle egrett (Bubulcus ibis) is a species of cosmopolitan ardeids in tropical, subtropical and warm temperate zones. It is associated with large herbivores, which are said to be cleaning parasites such as mites and flies, although surely what it does is to take advantage of the insects, worms and other animals that the livestock causes when removing the soil. The largest species of the group in Florida is the great white heron (Ardea alba), with all the feathers white, that almost reached extinction in those times. In the coastal areas of southern Florida there is a white variant of the great blue heron (Ardea herodias) which was one of the causes of the great hunts. The little egret (Egretta garzetta), well known in Catalonia, is also a white feather bird that, like other ardeids, forms colonies and builds platform nests above trees or shrubs, and on the reed beds when there are no trees or If in the woods there are many black rats. In Northwestern Europe it was extinguished at the end of the 19th century. Under protection, the populations have been rebuilt because it is a good colonizer species, but it did not reached Florida until 1953 and so it was not there when the great killings by feather hunters occurred.

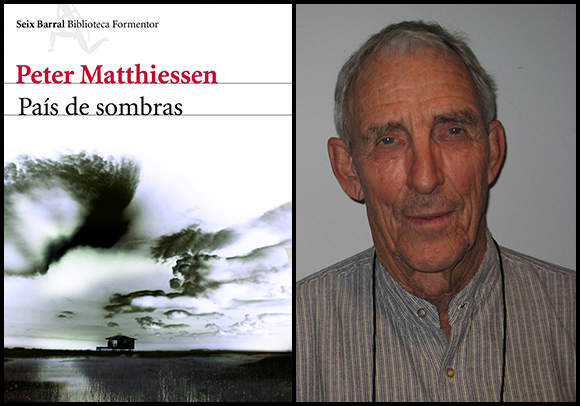

These massacres are described at the beginning of Shadow country, the enormous novel (892 pp.) by Peter Matthiessen, who won the National Book Award in 2008, a work that is among the most important books in recent decades American literature. This is the description he makes, in two paragraphs, of hunting and its effects:

“Plume hunters never shot cept in the breeding season when egret plumes are coming out real good. When them nestlings get pretty well pinfeathered, and squawking loud cause they are always hungry, then parent birds lose the little sense God give’em, they are going to come in to tend their young no matter what, and a man using one of them Flobert rifles that don’t snap no louder than a twig can stand there under the trees in a big rookery and pick the birds off fast as he can reload. A broke-up rookery, that ain’t a picture you want to think about too much. The pile of carcasses left behind when you strip the plumes and move on to the next place is just pitiful, and is a piss-poor way to harvest, cause there ain’t no adults left to feed them starving young’uns and protect ’em from the sun and rain, let alone the crows and buzzards that come sailing and flopping in, trear’em to pieces. A real big rookery like that offshore island the Frenchman worke, up Tampa Bay, four-five hundred acre of black mangrove, maybe ten nests to a tree-hell, mighy take you three-four years to clean it out, but after that, them birds is gone for good.

It’s the dead silence after all the shooting that comes back today, though I never stuck around to hear it; I kind of remember it when I’m dreaming. Them ghosty white trees and dead white ground, the sun and silence and the dry stink of guano, the squawking and shrieking and flopping of dark wings, and varmints hurrying without no sound—coons, rats, and possums, biting and biting, and the ants flowing up all them pale trees in dark snaky ribbons to bite at them raw scrawny things that’s backed up to the edge of the nest, gullet pulsing and mouth open wide for the food and water that ain’t never going to come. Luckiest ones will perish before something finds ’em, cause they are so many young that the carrion birds just can’t keep up. Damn buzzards get so stuffed they can’t hardly fly, just set hunched up on them dead limbs like them queer growths on the pond cypress limbs in the bare winter.”

The description is perfectly clear about an absolutely unsustainable use of resources and a total disregard for the lives of others (in this case birds, but humans often still behave same way against other humans). What Matthiessen describes is comparable to the massacres of elephants in Africa, bison in North America, young seals in Canada, whales in the oceans and so many other cases. And the reason, as in this case, is quite trivial: to decorate ladies' hats in the big cities, like in the case of elephants to produce ivory crafts, or in rhinoceroses to take their horn to make an aphrodisiac that, of course, does not work. The horn is nothing more than keratin, like our hair or our nails, but on the black market it can cost 60,000 euros per kilo. In the Far East, it is commonly believed that rhinoceros horn also cures arthritis, cancer or AIDS. In the zoo of Thoiry, near Paris, assailants killed a white rhinoceros, since its horn can cost 300,000 euros. This species has already been extinct in North Africa. In fact, in weight the horn is more valuable than gold or cocaine. For this reason, in some places the horns of the rhinos, white or black, are cut to save them from the poachers.

The good news is that the world's largest market, Hong Kong, has banned ivory trade from 2021 ahead. China also banned it last year.