If you don't get the water, you won't need it

Los Angeles and its great urban area (more than 18 million people) are in water suply problems since long time ago. At the begining of the 20th century, Owens Valley was drained among huge hiden economic interests that inspired the film Chinatown.

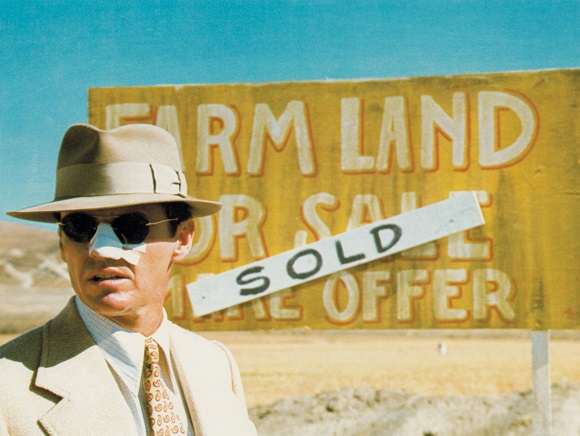

In Chinatown (1974), the famous film noir by Roman Polansky that a poll conducted by The Guardian considered as the best film in history five years ago (I do not share that opinion, although it is certainly a great movie), the main character (Jack Nicholson) is a detective who, in 1937, is hired by a woman to investigate a man (her husband, she says) who is the responsible for Los Angeles water supply services. This engineer is murdered and the detective then knows her real wife. The underlying reason for the crime is that the dead man discovered manipulations to divert important flows of water from the public network. The original title of the script was Water and Power. Those who diverted the water had previously purchased large plots of land that could mean a fortune if they could be irrigated.

Water is a driving factor in California, and in Los Angeles in particular. In a thirsty country, this is easy to understand. And it also explains that 96% of the old wetland areas of California have been destroyed to make crops... It is a pity that they have also been destroyed, in part, by urban settlings, but this is what has happened there and in many other places, like in our delta del Llobregat and Valencia’s “horta”.

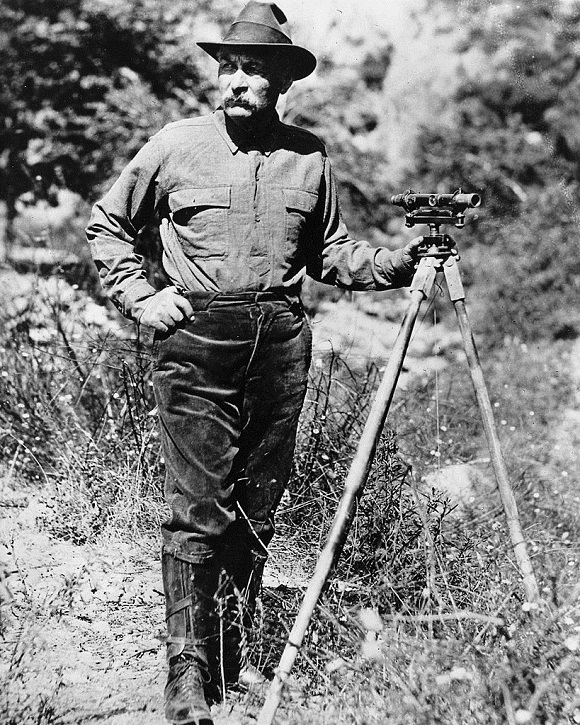

The character killed in the film is based on an engineer, William Mulholland, who was the responsible for the infrastructure that brought drinking water to Los Angeles, the works that triggered the California “water wars" among the small farmers of the Owens orchards, the cattle ranchers and the politicians, many of them corrupt, from the Los Angeles municipality. But Mulholland was not murdered. There was an important irrigation project in the Owens Valley at the beginning of the 20th century, but Mayor Eaton of Los Angeles bought the water rights in 1905 on a personal basis and then donated them to the city. He lied to the people of the valley, promising them that only the exceeding water would be sent to the city. The dispute came to President Roosevelt, who supported Los Angeles against the valley.

The Los Angeles population, who went from 100,000 to 320,000 between 1900 and 1910, was not informed that the water from the Owens river would first be taken to irrigate the San Fernando Valley, which was not a part of the municipality. As there was a rule that prohibited the sale of city water without the approval of 2/3 of the voters, what was done was to annex a large part of the San Fernando Valley to the Los Angeles municipality. This also allowed to raise the debt limit of the city, and so served to finance the aqueduct. A group of friends from Eaton with properties in the San Fernando Valley, using privileged information, contributed to generate the need for the aqueduct diverting water from the reservoirs to the sewer system to induce an artificial drought, and mounted a campaign in the media. All this clearly inspires Polansky's film, although it does no pretend to be historical. In 1913, Mulholland, who had been a co-worker and was a friend of Eaton, and who says the famous phrase “If you don't get the water, you won't need it”, which meant that if Los Angeles did not got water there would be no city), finally inaugurated the aqueduct that diverted the Owens River into the city and left the Owens Valley without water. It was a colossal work, with 164 tunnels. Between 1905 and 1925, most valley owners sold the land to the City of Los Angeles at a low price. In 1924, there was an attempt by the farmers to tear down the aqueduct, but they failed and Owens Lake dried up completely. The Inyo County bank went in bankrupt in 1927, ruining many people in the valley, and ending their resistance. In 1928, Los Angeles already owned 90% of the water rights, and Owens Valley’s agriculture died. In 1972, water was pumped from Owens and even some of the natural vegetation died also. After negotiations and many delays by the city, in 2006 the water’s flow to the valley was restored, but aquifer’s pumping has not ceased and the valley tends towards desertification.

Since the 1930s, the city already bought rights from an upper valley, Mono Lake. In 1978, a commission was created to protect this lake, since the environmental degradation was evident and the lake level had dropped 7.6 m below that of 1941. An agreement was reached to raise the level 6.1 m that still has not been entirely fulfilled.

A recent documentary, Water and power: a California heist (2017), by Marina Zenovitch, explains how, after 1990, some persons with great agricultural interests in the San Joaquin Valley took control of the water, leaving some people without no water to drink. A modern version of what Chinatown explains...

In 1928, the St. Francis dam, a work from Mulholland’s supply infrastructure, collapsed and there were about 450 dead, only a few hours after he and his assistant had made an inspection they considered satisfactory. Although there was no sentence against him in the trial, this ended his career. His figure is controversial, since he established the principle of public ownership of water in California and did much for the city, but his action led to conflicts and he committed, in addition to that one, other very serious errors. However, his name appears on different streets, highways and institutions. The best known is Mulholland Drive, in Los Angeles, which gives the title of a 2001 film by David Lynch acclaimed by critics.

Eaton and Mulholland wanted Los Angeles to be a great city. They had the oil discovered in 1892, which would make Los Angeles, three decades later, to become the city from where 1/4 of the world's oil was sold. And also, something occurred that they could not foresee: the film industry appeared. After the Second World War, the city grew a lot towards the San Fernando Valley. The 2010 census was of almost 3.8 million, but the metropolitan area and Greater Los Angeles have 13 and 18 million people. The case of the water wars between Los Angeles and Owens is just a small sample of a general fact: conflicts over water have been, are and will be very important in the world.

Safe freshwater’s needs increase very quickly but the availabilities do not. Beijing, one of the cities with the most serious problems of supply, pumps so much water from the subsoil that it begins to sink. Cape Town is, at the time I write, very close to a general supply’s breakdown. Bogotá depends on glaciers that are disappearing. Humans have already made wars for water and will do more.