On science, environmentalism and optimism

The human footprint on Earth is undoubted and inevitable to some extent . Science and technology, far from contributing to create more inequalities, must be able to mitigate these impacts, contribute to progress and improve the welfare of all the people in the world.

![]()

For Oriol.

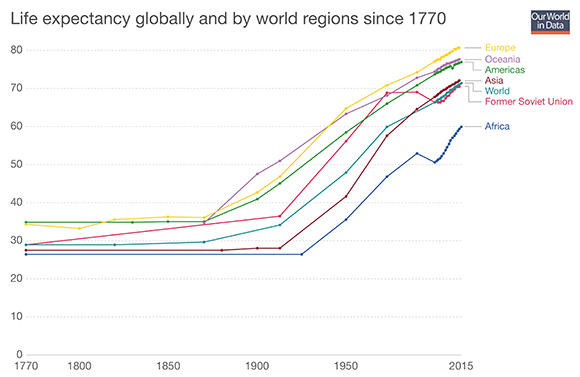

Steven Pinker seems an exaggerated optimist. Cognitive psychologist, professor at Harvard, in his latest book, "Enlightenment Now," analyzes the improvements in human well-being that have been implemented in recent history. It defends that the rational capacity to confront problems and the application of scientific knowledge have allowed humanity, as a whole, to have improved its levels of longevity, health, sustenance, security, democracy and equality rights. His rationale contrasts with a widely pessimistic view that proclaims that things are always going worse. Pinker identifies the beginning of that pessimistic vision in the romantic reaction to the enlightened rationalism that emerged in the nineteenth century and that survives today. In fact, in recent times an increasing current of opinion has been detected, questioning scientific knowledge. This opinion is often based on sensations or emotions, and on ancestral or traditional knowledge - whose main value is usually its own ancestral character, without a rational analysis of its causes or its effectiveness. The current profusion of so-called pseudosciences is part of this trend. Of course, it is good to question everything, and in the first place the scientific knowledge itself. Continuous self-evaluation is part of the essence of science. When technological capacity has advanced so much, it is not surprising a certain pendulum effect that questions science. Pinker bases his argument on demonstrating that opinions contrary to progress have little basis since quantitative data show improvements in the quality of life of humans as a whole, particularly since the 18th century. He uses an overwhelming amount of data, something that scientists appreciate, although some of these data are rather crude estimates when we go back in history or can be contrasted by other indicators.

The rational capacity to confront problems and the application of scientific knowledge have allowed humanity, as a whole, to have improved its levels of longevity, health, sustenance, security, democracy and equality rights. His rationale contrasts with a widely pessimistic view that proclaims that things are always going worse.

Pinker devotes a large chapter to the environment in his book. Following the general tone of his discourse, he rejects apocalyptic ecology as a variant of anti-enlightened romanticism. The most extreme vision would advocate a return to an Earth without human intervention, which implies the loss of some of our welfare standards. However, this extreme vision would hardly have many supporters because it represents discard certain advances that are desirable for the vast majority of humans, such as those provided by medicine that lengthens life thanks to often sophisticated technologies. Although not in its most extreme positions, the ecological vision has been supported by the scientific community, which has often used a reactive strategy, with desperate calls to radically change the functioning of our society. However, Pinker argues that the predictions of systemic collapse in our society have not been met: oil and other mineral resources that seemed destined to be exhausted in a short time have not. Ecological science does not admit that resources are infinite, and one of its paradigms is that populations deplete them, limiting their demographic growth. But ecology can also be applied to human societies when considering the flexibility of species in the use of resources and the natural mechanisms of recycling them.

However, there is no doubt that human activity, alters the Earth and its functioning, often with undesirable consequences. The recent recognition of the Anthropocene - as a period in the history of the Earth in which the human imprint extends to a global scale in the geological record - reflects this situation. In fact, the history of the Earth is indissolubly associated with life. The novelty is that our intervention is disproportionately fast and intense. The challenge is to take advantage of our intellectual, social and technological potential to minimize the problems that we create. It may seem nonsense to invest our effort to correcting mistakes that could have been avoided, but the reality is that we are more effective in dealing with problems that are pressing us than managing imponderables. Throughout most of the history of the human species each person has barely lived a few decades and their capacity to provide and manage resources has not surpassed much more beyond an annual cycle.

The challenge is to take advantage of our intellectual, social and technological potential to minimize the problems that we create. It may seem nonsense to invest our effort to correcting mistakes that could have been avoided, but the reality is that we are more effective in dealing with problems that are pressing us than managing imponderables.

In fact, the success of the concept of sustainability is amazing and is possibly one of the greatest achievements of our historical moment. Ethical considerations aside, the idea is extraordinarily complex - probably that is the cause of its limitations - since it implies a huge degree of temporal and spatial abstraction. To consciously project oneself to future generations - not to the children and grandchildren, but to the entire lineage per secula seculorum - is impossible for any other species, as it surely was to any ancestral hominid, whose evolutionary success was measured in the immediate generations. Deduce that resources can be depleted universally implies a global knowledge of the world completely beyond the reach of a tribe or a local society. When I hear about sustainability, I am moved by what it represents of ethical commitment and intellectual knowledge of our enlightened society, rather than by the recognition of uncertain traditional uses that, in most cases, did not have the capacity for long-term forecasting nor options to implement it.

Undoubtedly, the technological advance associated with the accumulation of wealth, consumerism and inequality promoted by the capitalist system generates great environmental problems, the shortness of energy and material resources, as well as the accumulation and treatment of derived waste. Many of these problems are quite predictable and we can devise alternative ways to minimize them before they occur. It is what the scientists declare in their manifestos, with a more or less catastrophic tone. But it is not the way the socio-economic model works, which prefers to delay as much as possible the loss of immediate benefits that long-term planning would imply. Pinker recognizes that the situation is not ideal and that we must engage ourselves thoroughly to solve those problems. In particular, it recognizes climate change as the main challenge we face due to its complexity and global scope: we will have to work hard to minimize its effects, completely transforming our way of obtaining energy.

When I hear about sustainability, I am moved by what it represents of ethical commitment and intellectual knowledge of our enlightened society, rather than by the recognition of uncertain traditional uses that, in most cases, did not have the capacity for long-term forecasting nor options to implement it.

One of the problems with this positive view of environmental problems is that socio-environmental systems are complex and change rapidly; any action involves collateral effects that are very difficult to predict in the medium term - there are studies that show that the ability to foresee in detail the future of society loses all reliability beyond five years, even for the most clairvoyant experts. We must therefore trust on our capacity for reaction. It's like a race in which we compete in an uncertain journey after some opponents that always go ahead: we are condemned to not win the race and we are right if keep advancing. It may seem frustrating, but it is the most normal thing in human activity: architects make constructions that they know will end up deteriorating and doctors fight to delay irremediable death. In the real world there are only sub-optimal solutions and the inertias to implement alternatives facing the future face the enormous power of uncertainty. Therefore, even adopting an optimistic vision, we must recognize the important role of catastrophic manifestos, normally based on the principle of prudence, to put in functioning feedback mechanisms that the social system, particularly the capitalist, would take too long to implement on its own. Bearing in mind that this system is regulated by laws and regulations that in the first instance control the institutions, these become a natural objective of environmental claims. Basically, it is a game of exaggerations to achieve a certain degree of commitment that redirects destructive socio-environmental forces. Nevertheless, we will always arrive later than is desirable, while environmental problems get worse and situations of suffering and injustice that are not acceptable.

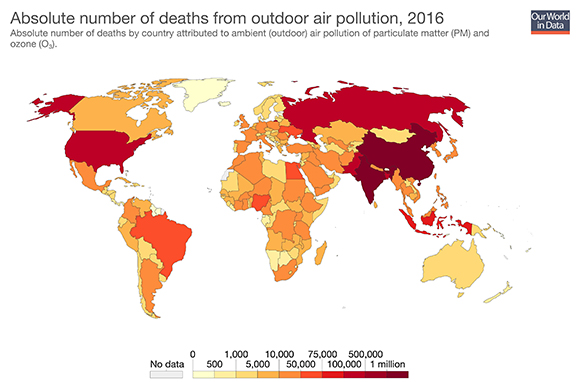

The capitalist system needs control mechanisms coupled with technological innovation and the advancement of knowledge. This is essential for the rational use of resources and to counteract the inequality between people. Karl Polanyi, in his classic book The Great Transformation of 1944, already pointed out that the private appropriation by a few of the wealth generated from technological innovation produces a reaction against progress on the social groups that suffer the resulting inequality. Surely the social prejudice against science that we observe today is related to this type of reaction. Even recognizing the uncertainty about the inequality estimators, some figures, such as that 1% of the world population has more wealth than the rest of the population, indicate that this is one of the biggest current problems. Pinker agrees, but he argues that current inequality is a pulse within its historical tendency to decline, and that even sectors that suffer inequality have seen their standards improved. This view underestimates the importance of emotional perspectives, since humans, we necessarily compare ourselves with our peers. Surely, we must accept that the wealth associated with scientific-technological progress is not distributed equitably, as resources do between different species, but an excess of asymmetry makes the system more vulnerable. If science is developed according to the illustrated program, and it defends that progress must affect the well-being of all humans, science should favor the mechanisms of control of inequality. There are studies that show a correlation between the economic level of societies and their level of environmental quality. Improving global environmental quality also increases the welfare of the poorest societies, and that will be particularly effective if scientific knowledge collaborates with regulations that otherwise will probably decrease the benefit of the richest percentile.

Improving global environmental quality also increases the welfare of the poorest societies, and that will be particularly effective if scientific knowledge collaborates with regulations that otherwise will probably decrease the benefit of the richest percentile.

Ecologists do not usually like the idea of progress based on unlimited growth. Any natural system tends to regulate when resources become scarcer or when external factors, such as disturbances, destroy an important part of the system. Therefore, ecological logics say that a system cannot maintain itself in a state of continuous growth. It is evident that the planet Earth is finite and that the model of continued growth of its resources is not viable in the medium or long term. Although the resource exploitation can be increasingly efficient or there would be substitutions of some resources by alternative ones, it is evident that an economic model based on continuous growth is not very consistent with the principle of regulated and limited growth that we observe in nature. However, Pinker identifies the idea of progress with the improvement of the welfare of people. We can easily agree with that. To that end, Pinker grants an essential role to the maintenance of economic growth. But, we know that the measures used to describe economic growth and its relation to welfare indicators are clearly inadequate. Imbricating the ecological and socio-economic models of growth is one of the challenges to be able to speak a common language. The idea of growth based on one or few indicators is inadequate to describe systems that become more complex and organized, such as socio-ecological ones. In addition, a priori, greater economic growth does not necessarily imply a growth in the exploitation of natural resources. The main question is not the system collapsing due to lack of a particular resource, but learning from evolution and ecology. Biodiversity has multiplied throughout history, while using of and generating new resources, altogether integrating the functioning of energy flows and matter in ecosystems.

In a recent book (The wizard and the Prophet), Charles Mann exemplifies the debate between the "prophets" like William Vogt, defenders of degrowth - followers of the book The Limits of Growth - as the only way to fight against the resource exploitation that has led to a seizure of most of the wealth by elites, thanks to the capitalist model, against the "wizards" like Norman Borlaug (Nobel Prize for his contributions to the agricultural "Green Revolution"), who defend the capacity of the system to eventually solve the problems. It is unfortunate that the evidence in one way or another is incomplete. The world has not collapsed, although environmental problems and inequalities continue to increase, while the ability to solve any future problem is just speculation or excess of confidence.

The illustrated program can be frustrated if scientists do not commit to the concerns of society and generate empathy, sharing the emotion of our discoveries and participating in the emotional aspirations of people.

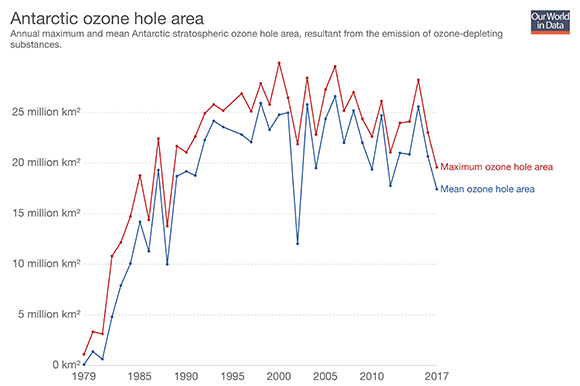

Pinker's opinions may seem reactionary at first glance. But I think that it would be to dismiss its main message. Pinker sees himself as the heir of the Enlightenment, whose program was to provide humans with a more satisfying life through the application of knowledge and rationality. But the fact that our society has been able to improve life expectancy, health, hunger or violence in a greater percentage of the population does not prevent, in absolute terms, the number of people suffering from unsustainable deprivation and that there are environmental problems, such as climate change, which has huge dimensions. But we should not blame scientific knowledge as the responsible of those problems. On the contrary, its application may alleviate the deficiencies in a system that feeds inequalities. The current trend to bring science closer to society, with all the reluctance that may exist about its rigor, goes in this line. But we could hardly defend the benefits of scientific knowledge if we do not recognize its successes. The famous ozone hole provides a good example. The reduction of the Antarctic ozone layer as a result of technological advances constitutes a serious threat to the health of humans, as well as for many other species. Currently the ozone hole is recovering thanks to the concerted action of politicians, scientists, companies and society in general. Obviously, it would be better if the problems had not born. But the great lesson we have learned is that when scientific knowledge is applied in a coordinated way we can alleviate those problems. This is very important to give meaning to the professional activity of those who work to preserve the environment. Otherwise, why dedicating oneself to this field the result is always disastrous? The answer is that we are effectively able to make improvements. Environmental awareness has increased in recent decades and attempting a rational use of resources while minimizing environmental impact has been placed on the agenda. We need a certain historical perspective to perceive this tendency. More than fifteen years ago Lester R. Brown in his book EcoEconomia made a series of perfectly rational and well-argued proposals, some of which, like the use of alternative energies, today have ceased to be utopias.

Unlike other social movements accustomed to highlight their successes, a reactive strategy has predominated in conservationism, focused on underlining the problems. Perhaps this is due to the very complex nature of natural systems, which makes it extremely difficult to obtain unequivocal successes. The situation can cause frustration to the conservationist, while apparently the scientists do not stop crying in the desert. But the alternative, the abandonment of knowledge, leaving the field open to beliefs based exclusively on opinions or faith, without a realistic foundation, as was the case before the Enlightenment, would lead to worsening our global environmental and welfare standards. Humans move more often by emotions than by reasons. And the power of emotions increases enormously when they are socialized and shared. Although knowledge has diminished a significant part of that uncertainty, the truth is that it needs the complicity of emotions. The illustrated program can be frustrated if scientists do not commit to the concerns of society and generate empathy, sharing the emotion of our discoveries and participating in the emotional aspirations of people. The idea was perfectly expressed by K. Hayhoe in a recent editorial in Science when he said that it is not enough for scientists to explain the facts if the interlocutor does not feels emotionally linked to the scientist (because they are neighbors, have children or share the same religion). Fortunately, the notion of nature is able to transmit positive values to our society. The ecology must share that feeling and interest in nature by making positive proposals and rationalizing catastrophism. At the same time, it must engage in two enormous tasks: on the one hand, to explain the risks that certain unfounded beliefs, more linked to esotericism than to reason, may become authentic paradigms; on the other hand, to help show how the current use of the planet's resources, based mainly on private profit, is not compatible with the well-being of human society as a whole.