Extreme drought causes shrublands and grasslands to capture 35% less CO2

A study published in the journal PNAS has revealed that short-term droughts (lasting a year or less) of extreme intensity reduce the carbon storage capacity of shrublands and grasslands by 35%, a figure higher than previously estimated. The research also found that the loss of plant growth in such droughts is 60% greater than in the less severe droughts that have been more common historically. “That growth rate is a key indicator of ecosystem health and is related to the ability to capture carbon dioxide,” explained CREAF-based CSIC researcher Josep Peñuelas, one of the study’s authors. Given that shrublands and grasslands cover 30 to 40% of the planet’s terrestrial surface and account for over 30% of the global carbon stock, calculating exactly how future droughts will affect them is crucial, as Peñuelas went on to say.

“While such droughts have been once-in-a-century events in the past, climate change could lead to them happening every two to five years.”

Extreme droughts entail an ongoing lack of precipitation and, despite usually lasting less than a year, can have devastating effects, according to the study’s authors. The researchers warn that while such droughts have been once-in-a-century events in the past, climate change could lead to them happening every two to five years. Areas currently experiencing extreme droughts include Catalonia, the Cerrado region in Brazil, and the southwest USA.

The International Drought Experiment

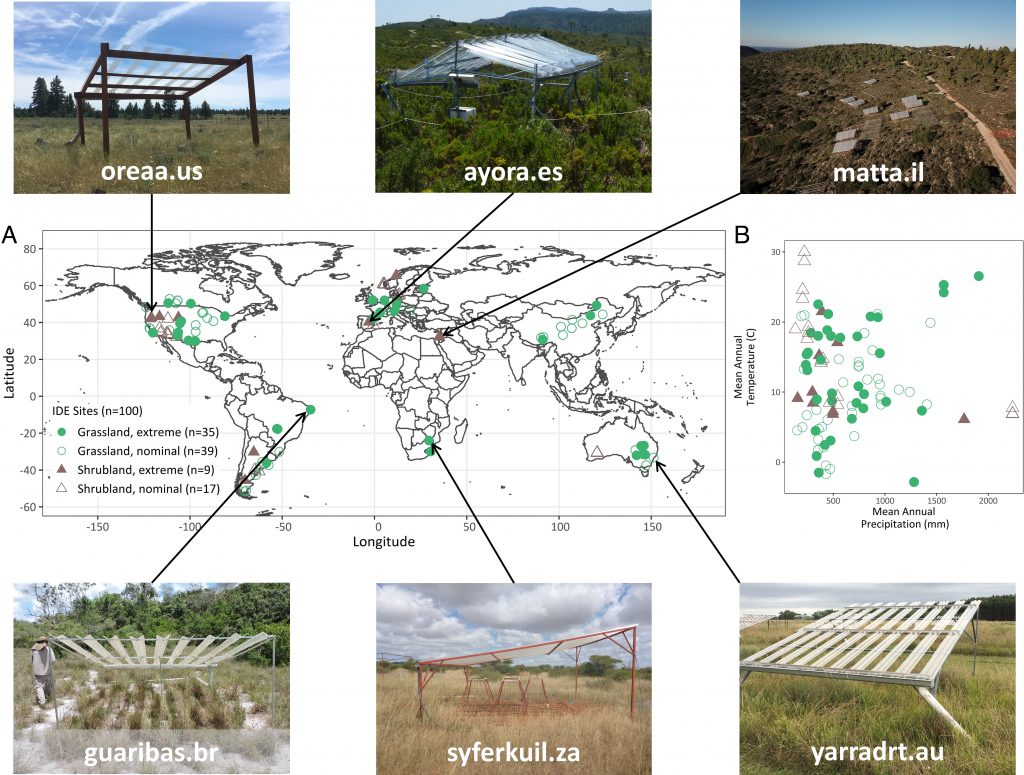

For their research, the team behind the study established the International Drought Experiment, encompassing a hundred sites, with different climate, soil and biodiversity conditions, across six continents. They recreated an extreme drought lasting at least a full growing season at 44 of the sites, and a less severe drought at the other 56. After a year, they analysed aboveground net primary production to determine how much growth had been lost.

The study’s lead author was Melinda Smith, a professor in the Department of Biology of Colorado State University. She remarked that the results showed the losses recorded after a single year of extreme drought to greatly exceed those previously reported for grasslands and shrublands.

The results showed the losses recorded after a single year of extreme drought to greatly exceed those previously reported for grasslands and shrublands.

Specifically, the researchers found the losses to be 1.8 times greater than had been thought for shrublands, and 1.5 times greater for grasslands. “That is almost double previous estimates,” emphasized Peñuelas.

The areas most vulnerable to future droughts

The study’s data also reflected variability in the way different sites respond to drought, with drier and less diverse ecosystems proving less resilient and more vulnerable. “We saw that areas with a drier climate, like some Mediterranean countries, will be affected more,” stated Peñuelas.

Led by researchers from Colorado State University, the study involved more than 170 scientists from institutions across the world, including Josep Peñuelas and CREAF researcher Romà Ogaya.

Referenced article: Melinda D. Smith, Kate D. Wilkin, et al. Extreme drought impacts have been underestimated in grasslands and shrublands globally. PNAS. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2309881120