Deforestation behind irreparable bird loss in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest

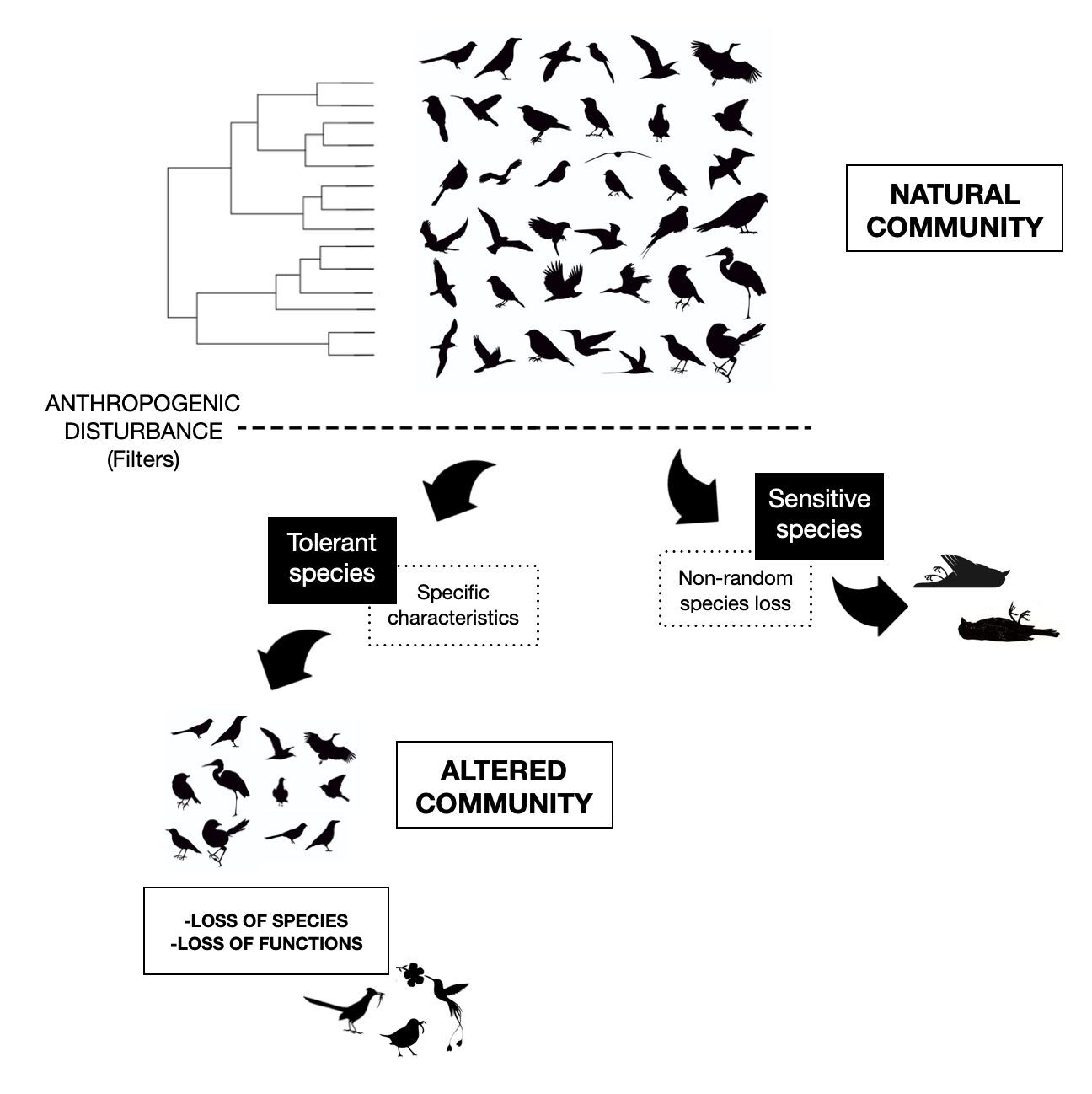

Extending along Brazil’s coastline and as far inland as parts of Argentina and Paraguay, the Atlantic Forest is a biodiversity hotspot. Over the years, however, it has been subjected to severe deforestation to make way for a mosaic of agricultural land, pastures and urban areas. A recent study, published in the journal Conservation Biology and led by CREAF and São Paulo State University’s Bioscience Institute, shows that this new, heterogeneous landscape is having a devastating impact on certain specialist bird species that depend on the forest to survive and play crucial roles in pollination, seed dispersal and pest control. According to the study’s findings, the species in question are irreplaceable, in that the functions they perform in the forest cannot be fulfilled by either generalist birds, which are more resilient to change, or the birds that are colonizing the new landscape.

Specifically, the team behind the study determined that 58 of the 539 species they analysed are exclusively found in areas where forest cover exceeds 70%. “That’s worrying, given that only a tenth of the Atlantic Forest is so well preserved at present,” remarks lead author Lisieux Fuzessy, a researcher at São Paulo State University and at CREAF at the time of the study. To conduct their investigation, the team used an extensive database containing records of the number of species and their abundance in various locations in Brazil. They then compared that data with satellite images of cities, pastures, croplands and forests to establish which species are currently found in each habitat and what functions they perform. “We didn’t carry out a temporal analysis; we analysed a snapshot of the present situation,” explains Fuzessy.

The black-fronted piping guan: a seed disperser and Indigenous symbol

The black-fronted piping guan (Pipile jacutinga) is a unique, endangered bird that lives in the heart of the Atlantic Forest. It is, says Fuzessy, a prime example of the specialist species that are being lost. A large, chicken-like bird that inhabits densely forested areas, it feeds on fruits and plays a vital role in the dispersal of seeds, especially those of the Euterpe palm trees that cover the understorey. It is clear that the forest and the black-fronted piping guan need each other: the bird not only feeds on the fruits of the palms but also nests and shelters among their leaves; in return, it spreads their seeds in its droppings. And, besides its ecological function, the black-fronted piping guan (called yakú-apetí or ‘white yacu’ in Tupi-Guarani, in reference to the white feathers on its head) has cultural value for Indigenous communities. Some peoples consider it a symbol of beauty and freedom, for instance, and it is also believed to connect nature with the spirits of the forest.

Another prime example of an at-risk seed disperser is the white-winged cotinga (Xipholena atropurpurea), which, furthermore, also eats insects and thus controls their populations. Other affected endemic species include some that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) deems vulnerable, such as the ochre-marked parakeet (Pyrrhura cruentata) and Temminck’s seedeater (Sporophila falcirostris), and some it classes as near-threatened, such as the elegant mourner (Laniisoma elegans) and the solitary tinamou (Tinamus solitarius).

“These birds’ interaction with the Atlantic Forest is a clear example of interdependence between birds and the forest. Through our study, we want to call for conservation strategies to take the specific functions of each species into account too, rather than just the total number of species in an area”, LISIEUX FUZESSY, primera autora del estudio, investigadora de la Universidad de São Paulo en Brasil y del CREAF en el momento del estudio.

Some are lost, others gained

The study’s results also show that new species are colonizing the mosaic of habitats formed by cities, agricultural land and pastures, including some exotic species, such as the rock dove (Columba livia) and the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). In fact, of the 539 species analysed, 107 are exclusively found in such habitats. Nonetheless, the study ascertained that well-preserved forests still harbour 15-25% more species than the mosaic in question.

“Some scientific studies consider this habitat heterogeneity to be positive because it allows more species to arrive; that’s partly true, but it doesn’t compensate for the loss of specialist species vital to the forest’s wellbeing,” concludes Fuzessy.

The study was led by Fuzessy, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) postdoctoral fellow at CREAF when it was carried out. The CREAF researchers Daniel Sol, Laura Cardador and Joan Maspons also participated in it, along with Sandrine Pavoine, a researcher at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation Sciences (CESCO) in France. The study was part of a project that received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme under a MSCA agreement, as well as from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the Government of Catalonia’s Agency for the Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR), and the European Union’s COFUND programme.

Referenced article: Fuzessy, L., Pavoine, S., Cardador, L., Maspons, J., & Sol, D. (2024). Loss of species and functions in a deforested megadiverse tropical forest. Conservation Biology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.14250