Ecology and rural depopulation

Rural depopulation has earned a place on the political and social agendas. The government of Spain and the different Autonomous Communities have secretariats, departments and programs to reverse rural depopulation or at least mitigate it. Even the European Union develops strategies and action plans. There are quite a few reasons for this. There are social reasons, since depopulation is a driver of inequality due to the decrease in services that declining rural populations receive. There are cultural and emotional reasons that link personal and collective roots to a landscape that is disappearing. There are economic reasons, since there are resources in the territory that are no longer exploited. There are environmental reasons since the ability to control certain impacts on the environment, such as forest fires, is reduced. There are geopolitical reasons, since society loses sovereignty over depopulated territories, opening an opportunity window to other power networks, such as crime or other political agents, to come to control them.

The loss and aging of the population in many rural areas began in the middle of the last century

The loss and aging of the population in many areas where until a few decades ago the primary sector predominated is not a recent phenomenon, but it ather began in the middle of the last century in Europe and in the eastern regions of North America. But the situation has worsened in recent times, or at least that is how public opinion and political agents have perceived it. Consequently, initiatives to consolidate local populations and activate the economy of rural areas appear. The outcome of these initiatives is uncertain, although we know in advance that the effort is insufficient and inadequate for any of the parties. However, it is surprising that the ecological dimension of rural depopulation has been ignored or treated very superficially, at a time when environmental issues have become one of the axes of socio-political and economic action. How does rural depopulation affect ecological processes and environmental quality? What does ecological knowledge contribute to the understanding and management of the phenomenon? These issues are rarely discussed.

Let's briefly review the history of rural depopulation under an environmental perspective. In Europe, and particularly in the Mediterranean region, the transformation of ecosystems by human societies dates back at least to the Neolithic. Since then, the landscapes have been changing following the ups and downs of these societies. When population density and technological capacity have been greater, these transformations have been more profound. Many forests were cut down to make way for pastures and crops, and most of the surviving forests were left depleted in species, dominated by young trees while wood and firewood were extracted or charcoal was made. The wetlands dried up, the rivers were channelled and their waters were extracted for irrigation. Many soils eroded, despite efforts to retain them in terraces. Ecological webs were simplified and transformed according to human uses. Undoubtedly, a greater proportion of the human population was more in touch with natural processes than today, but they shaped them according to their convenience, knowledge and ability, usually simplifying them. Simultaneously, evolutionary and ecological processes continued. The species most adapted to humanized environments proliferated and new lineages appeared, some of them directly from the hand of humans. New, more open habitats were generated, which became occupied by a biota that found adequate conditions and resources there. For biodiversity, the balance of this history of our landscapes is ambivalent. Some important components have been lost and the biotic interactions networks have been simplified, while new opportunities for some species have been generated in what we can consider semi-natural environments. This balance leans towards more negative effects when the impact on the territory intensifies, leaving fewer semi-natural elements, homogenizing large areas of the territory.

In any case, it is important to understand that in these territories the natural and social systems have not been disconnected. In fact, both are part of a socio-ecological system that integrates them through flows of energy, matter and information. Even urban agglomerations depend on natural processes that operate far away, such as those that determine the climate or the availability of water and energy. This connection between rural and urban environments also occurs in cultural and emotional aspects. We maintain intergenerational links with the landscapes of our ancestors, while cities continually generate new cultural references that arrive to the countryside. Although we mostly live in urban centers, we are still animals that evolved in open spaces and we seek for plants and animals to grow in our immediate environment, domesticating them to our willingness. In turn, those of us who live in rural environments depend on technological developments, cultural artefacts and power structures created when population density reaches a certain dimension. The inhabitants of towns need health, technological and even economic services that are generated and redistributed to a large extent from urban agglomerations. The urban and rural worlds are connected, they are part of a continuum, despite the efforts of politicians and narrative creators to confront them. A certain benefit can be obtained from promoting this confrontation, but in the medium term it is a serious mistake to tear apart the entire socio-ecological system. An ecosystem vision allows us to understand and formalize these interconnections.

This ecological perspective is also manifested when we analyze the effect of rural depopulation on environmental quality. In general, higher human density tends to have a negative impact on biodiversity. Therefore, at first glance, rural abandonment would favor the recovery of biodiversity. However, things are not so simple. Current rural landscapes are the result of a co-evolution in which human societies and natural processes have participated in an integrated way, not superimposed or opposed. We can talk about cultural landscapes, or in some cases semi-natural, in which elements of biodiversity that deserve conservation have been accommodated. This is the case of weed plants that coexist with crops and enrich food webs, control pests and promote pollination and dispersion. Or bird species that need open spaces which find in agroforestry landscapes.

The ancestral transformation of natural systems has simplified food webs

On the other hand, the ancestral transformation of natural systems has simplified food webs, stripping them of key pieces that we cannot fully restore, or introducing new elements - such as exotic species or equipments that interrupt the course of rivers - that are profoundly transformers. Importantly, ecological systems are historical, they do not return to previous situations, with conditions, such as climate, that do not occur again. That does not mean that we should not try to incorporate elements of naturalness, such as the multifunctional complementarity that biodiversity provides. These elements of naturalness better regulate the complexity of socio-ecological systems than intensification and homogenization, which may be more efficient for certain objectives, but do so to the detriment of the functioning of the system as a whole. Agroecological systems, as opposed to intensive agriculture, based on water and nutrient inputs and monovarietal crops, are a good example. The decrease in human activity in the territory allows natural processes to be re-established to a certain extent. But these processes work with severed natural elements and must be coupled for the system functioning. For example, initiatives to carry out massive reforestation in depopulated areas can increase carbon sequestration with the intention of helping to mitigate climate change, but the effect of vegetation on the climate system does not depend solely on its capacity to fix carbon, but also the control it exerts on water flows - accelerating its cycle - and energy - absorbing radiation that is not reflected into the atmosphere -. Not to mention what massive plantations means depleting biodiversity.

Biodiversity is not the only environmental aspect affected by rural depopulation and the actions proposed to reverse it. The use and regulation of water resources, soil conservation, the storage of carbon stocks and their effect on the climate, or the pollution of soil, water and air are some aspects to be considered. Thinking that depopulation will automatically relax the anthropic pressure that negatively impacts these aspects is too simple. Once again, two basic facts need to be incorporated: (1) we start from historical systems deeply modified by human action, made up of pieces with a degree of altered naturalness; (2) it is necessary to adopt a systemic vision with human societies integrated into the functioning of the whole system. Depopulation opens windows of economic opportunity, for example, for energy installations, communication routes, industries, agricultural operations and polluting urbanizations that consume energy and water resources. These activities take advantage of the low population density so that their impacts affect fewer people. Its defenders argue that the economic benefits will trickle down to the resistant population. But it is known that most of the economic benefits end up far from these territories and in many cases are generated during the construction of the facilities. In any case, these intensive uses of the territory do not consider the territory multifunctionality. And we have learned how environmental large problems arise when we focus on achieving maximum efficiency in a single type of benefit.

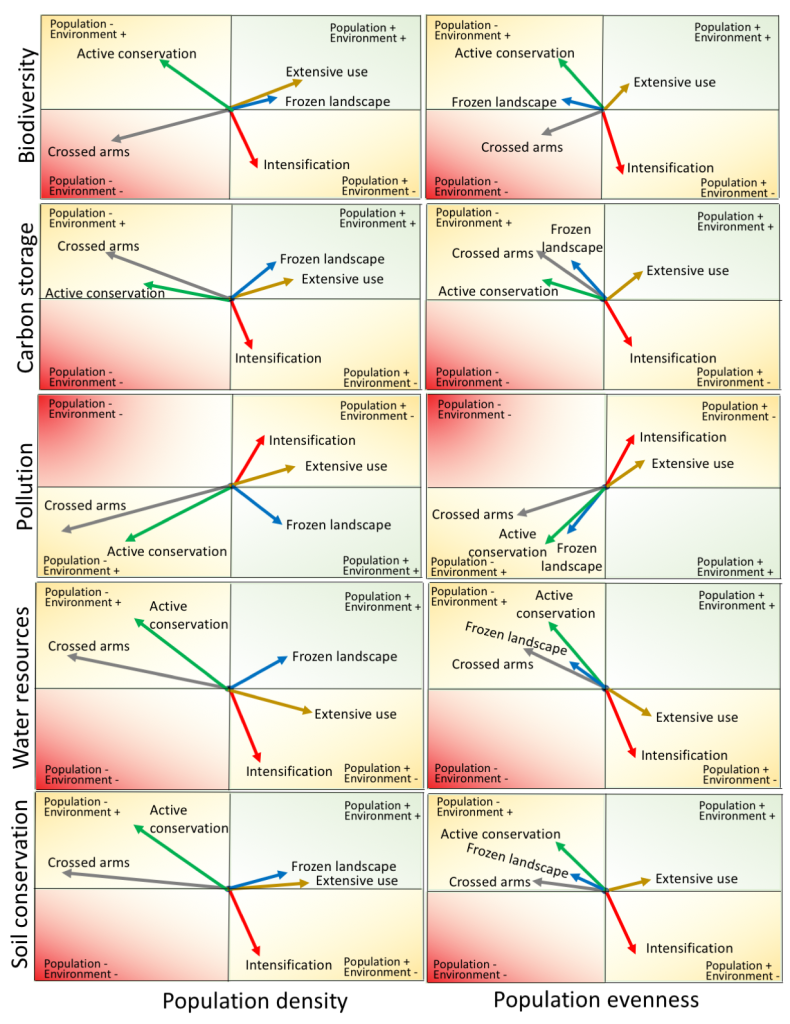

At first glance, it does not seem easy to deal with this multifunctionality of landscapes and the ecosystems they host. But there are formulas. For example, representations of the system's trajectory can be built in a virtual space defined by axes that on the one side correspond to the population density in the territory and on the other side to the quality of the environmental parameters (see Figure). Thus, assuming that the current situation remains, the rural population would continue to decrease while the loss of biodiversity that has occurred in cultural ecosystems would hardly be compensated by the reincorporation of elements lost long ago. We have recently applied this approach to the interior regions of Spain by comparing the vectors that describe the trajectory of the system under different management alternatives including (i) the maintenance of the current situation, or the implementation of (ii) active conservation policies, with an important role of renaturalization (rewilding), or (iii) policies that seek to retain a mosaic of habitats with a static vision, (iv) an extensive and sustainable use of the territory and (v) an intensification of the use of depopulated territory, as described above. (Lloret et al. 2024, People and Nature 2024). In addition to biodiversity, these trajectories have been estimated for different environmental quality parameters, such as carbon storage, the absence of pollution, the availability and regulation of water resources, and soil conservation.

The result of the exercise indicates that there is no alternative that optimally maintains the demographic and environmental quality parameters simultaneously. We have already seen that the current situation leads to demographic loss without reversing many of the inherited environmental problems. But scenarios based mainly on conservation criteria do not allow us to substantially change the trend of demographic decline either. The compromise solution would be an extensive use of the territory that maintains economic activities, establishing a population, that in addition to taking advantage of the technological possibilities that facilitate the establishment of long-distance information communication, were environmentally sustainable. These activities are often related to natural resource management, which should be based on natural processes and cultural values and natural heritage. The environmental impact would not be zero, but it would be much less than that the impacts caused by intensification. Curiously, some of these intensive activities are associated by public opinion with traditional visions of the rural environment. This is the case of farms or large irrigated lands that can consume a large amount of water and can be as much polluting than industries that are usually associated with the urban world. Once again, the borders between the rural and urban world are blurred when we adopt a functional, systemic vision.

In summary, it is necessary to integrate the ecological vision and the knowledge we have about the functioning of natural systems in the assessments we make of the challenges posed by rural depopulation. This approach must consider the entire socio-ecological system. It is not an easy task, since it is a highly complex system, in continuous transformation. But we have ecological tools and knowledge that should contribute to the debate and to provide fundamental elements when establishing agendas and action plans to confront rural depopulation.