Mature forests, small vaccines against global change

On the occasion of the International Day of Forests we present an in-depth report on mature forests. What are they and why can they function as vaccines against climate and global change? Do they require management? Which one?

Intensive logging, large fires, neglect. If we think of a forest that has not received any high intensity disturbance in Spain in the last 100 or 200 years, we will hardly find it. And the fact is that forests have also been suffering recurrent crises for many years. Crises that have to do with our activity and to which the effects of climate change are increasingly being added. How can we remedy this? By finding, conserving, managing and strengthening the small strongholds of resistance that are distributed throughout the territory and that act as small vaccines against the crises: mature forests.

Even in their most mature stages, mature forests continue to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They are also a hotspot of biodiversity and retain moisture better.

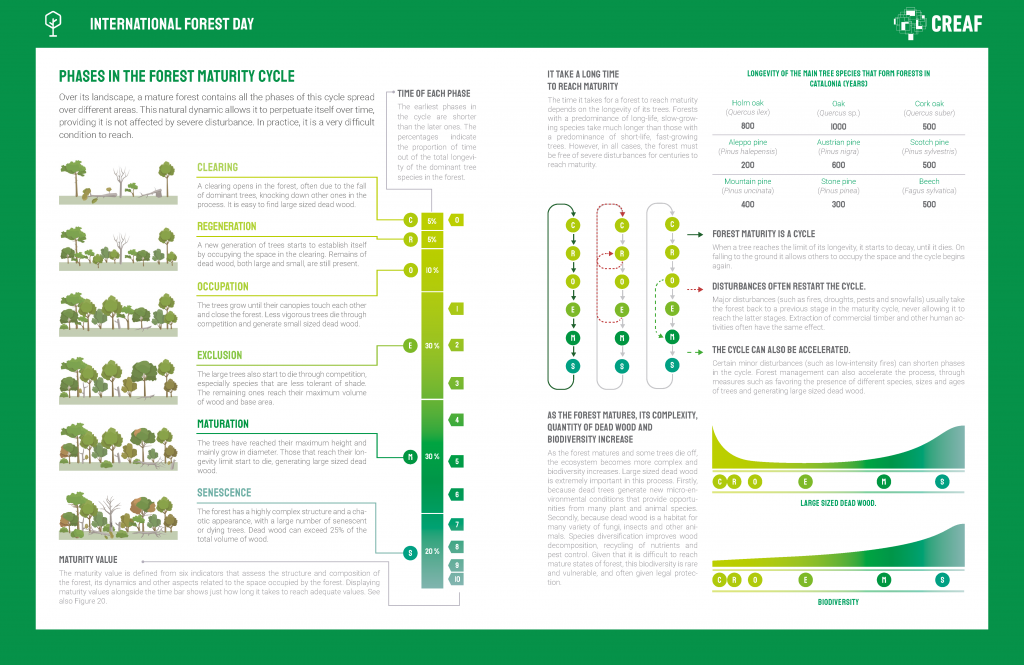

In general, we speak of a mature forest when we are dealing with hectares of landscape that have evolved freely without much human footprint and free from extreme phenomena such as hurricanes or fires; conditions that have allowed them to establish unique fauna and flora dynamics and to enjoy old trees of exceptional size. It is precisely these qualities that are the key to the fight against climate change, explains CREAF researcher and expert in mature forests Jordi Vayreda: "Apart from supporting a high level of biodiversity, these forests maintain environmental humidity better and resist drought and erosion more effectively. In addition, the humidity itself, the thick wood and the diversity of sizes and shapes of the trees help to ensure that fires that do occur are not so catastrophic. In addition, even in the more mature stages, mature forests continue to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere". Along the same lines, Lluís Comas, a CREAF officer, adds that "mature forests generate large quantities of dead wood -on the ground or standing- from trees that have already died of old age and which are the refuge and food for many invertebrate species that represent 99% of the forest's animal biodiversity. People associate this dead wood with more pests and it's quite the opposite, because the more diversity there is, the more predators there are to control them”. If we locate all this resilience in different parts of the territory, it will be like vaccinating it against changes.

Unfortunately, the experts explain that this situation is very difficult to find in the Iberian Peninsula, as "there is no forest that we have not touched for 200 or 300 years to make use of it. Not forgetting that the Mediterranean region is very dry and favourable to fires. A pine forest would need 400 years or more to reach a mature state and it is almost impossible for it not to burn in such a long time", according to Vayreda. They also warn that the environmental conditions in which the forest grows also play a role. The same tree can take 300 years to become mature in deep, nutrient-rich soil and much longer in poor soil. So what do we do?

Can we be architects of forest ageing?

Although there are no strictly mature forests in the Iberian Peninsula -and, in fact, there are very few in the whole of Europe- there are two alternative figures that come close and to which we should direct our efforts: mature stands and some singular forests. There are small pockets that fulfil many of the characteristics of a mature forest, which we know as mature stands. However, the numbers in these cases are not encouraging either: in the Mediterranean, of all existing forest stands, less than 1% are mature. Lluís Comas adds that "there is also the case of some unique forests, which only fulfil some of the properties of maturity, but which are larger. A good example would be an old pasture abandoned many years ago, which still has old trees and is combined with the new young forest that is advancing".

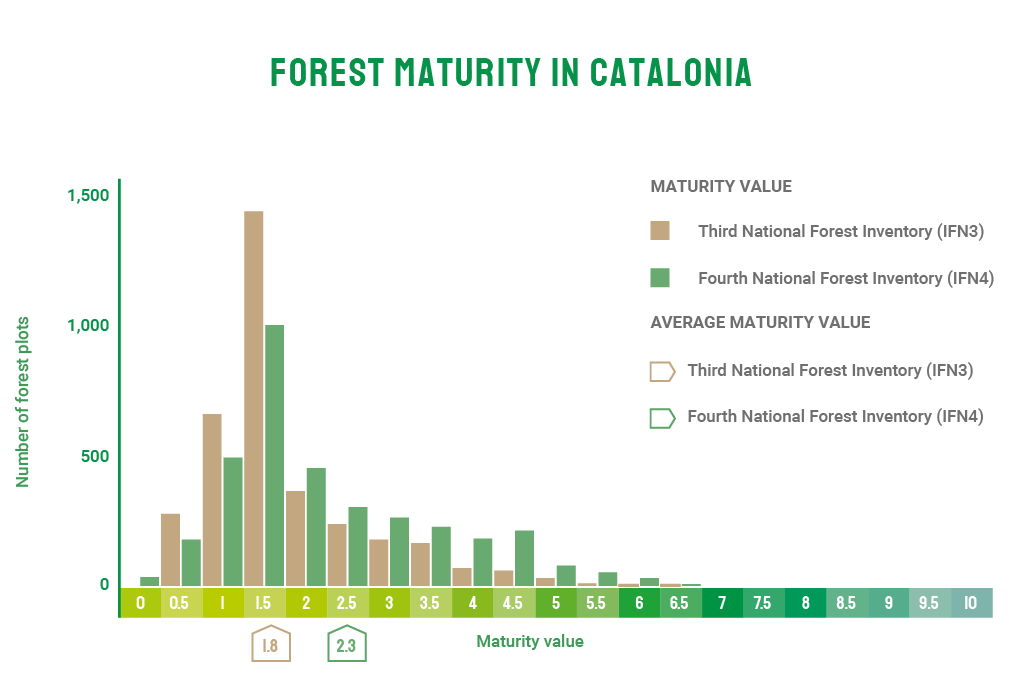

Catalonia has been a pioneer in Spain in locating and characterising unique forests and mature stands, and some projects have been running for more than fifteen years, such as the forest inventories of La Garrotxa, Alt Pirineu and Montseny. With regard to the Montseny massif, the Natural Park's forestry engineer, Anna Sanitjas, warns us of the small number of mature stands that remain, "only 0.02% in the latest inventory of 2020". The first exhaustive work cataloguing these unique forests appeared in 2011 under the name Inventory of the Unique Forests of Catalonia, and was coordinated by CREAF on behalf of the Catalan Government. More recently, in December 2020, the State of Nature in Catalonia 2020 report was presented, which devotes a special section to assessing the state of maturity of our forests. According to this document, on a scale of 1 to 10, forests have gone from having a maturity level of 1.8 to 2.3 in the last 25 years (data that can still be improved).

However, that is not all. It is not only mature forests - or stands - that we need to find and take care of. If we do not have many mature forests or stands, we can manage and restore forests to achieve mature characteristics. "Forests that are at a pre-mature level, you have to decide whether not interventing and close-to-nature forestry to evolve over time, or whether to help them to reach maturity earlier. For example, cutting or ringing some trees to generate dead wood, or opening small clearings in the homogeneous beech forests to diversify the age of the trees. In the case of Montseny, pilot tests have been carried out in the Matagalls and the results are very positive," explains Sanitjas.

Biodiversity has the key

"One thing is to abandon forests and another is to have mature forests and manage them with free dynamics. It requires planning and responds to clear objectives".

While it is important to improve the maturity of some forests and conserve those we already have, other types are also needed: forest science seeks balance. "A courageous policy is needed to conserve our natural heritage, but obviously not all of Catalonia must be a mature forest. We have to look for a mosaic where they coexist with younger ones and with open spaces, such as pastures and crops. It is important to make our territory more resistant and resilient in the face of climate change," says Anna Sanitjas. The expert also reminds us of the problem of forest abandonment that we have experienced since the 1950s and stresses the difference with mature forests: "one thing is the abandonment of forests, which is a national problem, and another is to have mature forests and manage them in a dynamic way. It requires planning and responds to clear objectives, for example, it is necessary to assess which ecosystem services will be maintained in each case (biodiversity, CO2 fixation, timber, leisure, fire prevention, etc.)".

This line of work is the focus of some of the projects being developed in Spain, such as LIFE Biorgest and the recently completed LIFE RedBosques. The latter is coordinated by Europarc-Spain and in which CREAF has participated in order to identify, among other objectives, mature forests throughout Spain as reference models for research and management. The information extracted has been synthesised in a practical manual which is available in Castilian. Biorgest, which is led by the Consorci Forestal de Catalunya, and also with the participation of CREAF, seeks to incorporate biodiversity into the forest management of young and mature Mediterranean forests. The aim is to improve their conservation status as established by the European Union with the Habitats Directive.

Seek, conserve, manage and enhance. All these measures may even seem few in the face of all the crises facing forests, but they are the beginning. The first step in a forestry strategy that should lead us to strengthen the vaccines against the forest crises that mature forests represent and thus achieve herd immunity.