Trees capture methane from the atmosphere thanks to microorganisms that live in their bark

Sometimes, tweaking experimental conditions can produce a scientific breakthrough that radically changes our understanding of the world. That is exactly what happened in the case of a study published today in the journal Nature, which reveals that, contrary to what was previously thought, trees consume methane, a greenhouse gas responsible for around 30% of global warming. Researchers typically use the first metre of a tree’s trunk to measure methane fluxes; within that height range, trees emit the gas in question into the atmosphere. However, in this study, which was led by the University of Birmingham and involved CREAF, measurements were taken higher up, rather than just near the ground, leading to the finding that, at heights of approximately two meters and above, bacteria living in bark absorb far more methane from the air than trees release into the atmosphere. “We estimate that the planet’s forests have the potential to absorb between 24.6 and 49.9 Tg of methane, a similar amount to that captured by soils worldwide,” remarks CREAF researcher Josep Barba, one of the study’s co-authors. Barba and his colleagues also found that forests in warmer, more humid climates, such as tropical ecosystems, have the highest methane uptake rates. “That is because the microorganisms are more active in those conditions,” he explains.

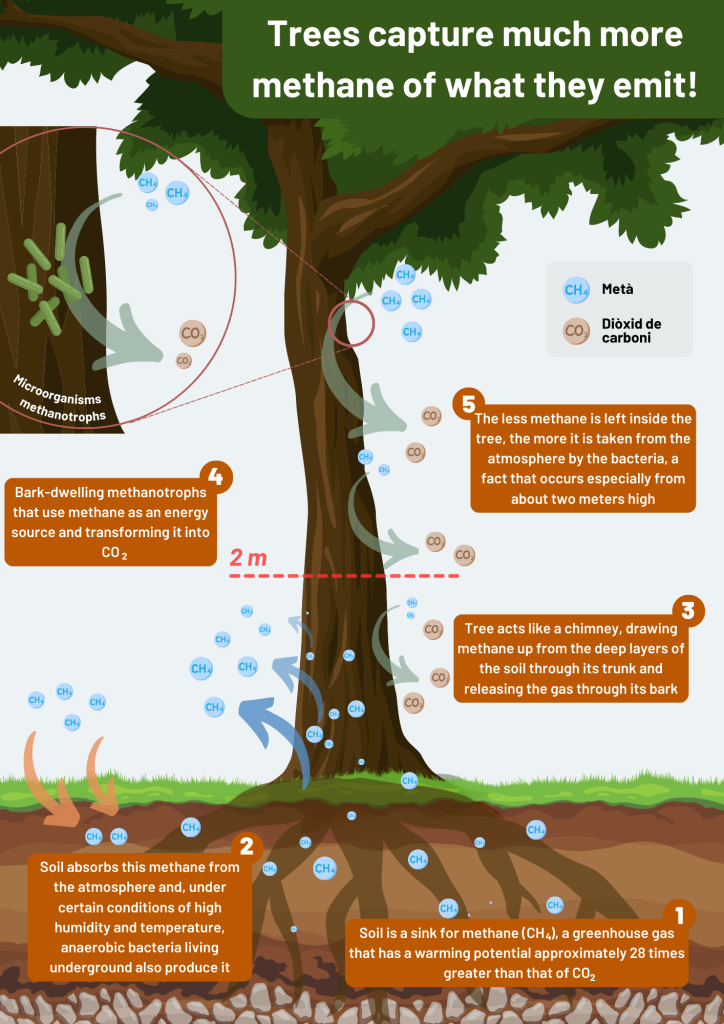

According to the researchers, the phenomenon they discovered is attributable to the role of bark-dwelling methanotrophs, bacteria that use methane as an energy source. Such bacteria begin consuming methane from outside a tree as the amount of the gas inside it diminishes; that occurs at the two-metre mark and above.

"A tree acts like a chimney, drawing methane up from the deep layers of the soil through its trunk and releasing the gas through its bark. So, the higher up the trunk you go, the smaller the amount of methane remaining within it gets."

JOSEP BARBA, CREAF researcher Josep Barba, one of the study’s co-authors.

Beyond the two-metre mark, there is less of the gas inside the tree and the bacteria start to consume it from the air outside. “The overall result is that trees absorb more methane than they emit,” states Barba.

An intriguing experiment

"We observed that tropical forests capture the greatest amount of methane, followed by temperate forests and then boreal forests"

The study’s authors conducted their research in tropical forests in Panama and Brazil, where conditions are warm and humid; in boreal forests in Sweden, which grow in cold temperatures and receive little rain; and in temperate forests in England, which, in terms of climate, represent an intermediate point between tropical and boreal forests. The research team analysed hundreds of trees of various species using a simple yet intriguing method. They attached measuring chambers to tree trunks to detect gas emission and absorption via bark in real time, and took measurements at different heights. They also extracted wood samples from the inside of some trees to assess how much methane they contained and how much was being consumed by bacteria. “We observed that tropical forests capture the greatest amount of methane, followed by temperate forests and then boreal forests,” reports Barba. “More specifically, tropical forests capture approximately 10 times more methane than temperate forests, and around 20 times more than boreal forests,” adds the scientist, who has already begun to take samples from a number of beech, oak and pine forests in Catalonia.

The study’s data also indicate that within a given forest, some species capture more methane than others, probably owing to differences in wood properties, such as wood density or the diameter of the conduits that carry water and nutrients around a tree. However, Barba notes that the aspect in question was not examined in depth in the study and warrants further research.

Forests: more valuable than ever

By adding trees’ potential for absorbing methane to their well-known ability to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, the study has further enhanced the importance of forests in climate change mitigation plans, making trees 10% even more better for climate than we previously thought. As Barba points out, methane and carbon dioxide are the two gases that contribute most to global warming. The study could also lead to a change in perspective in reforestation strategies. While some new forests are inefficient carbon sinks, because they are made up of young trees with little biomass, the key consideration in the case of methane is not how mature a forest is but how much bark it has to interact with the atmosphere. “It doesn’t matter if the trees are young; as long as there are plenty of them, there will be a lot of exposed trunk surface and the potential for capturing methane from the atmosphere will be high,” explains Barba.

“The Global Methane Pledge, which was launched at the COP26 climate change summit in 2021, aims to reduce methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030,” remarks Vincent Gauci, a researcher at the University of Birmingham and the study’s lead author. “Our findings suggest that planting more trees and curbing deforestation should be major parts of any effort to achieve that goal,” he concludes

The study was carried out by an international consortium of institutions, comprising the University of Birmingham (the study’s leader), the University of Lancaster, Lancaster Environment Centre, the University of Oxford, and The Open University (all UK); Northern Arizona University (USA); Linköping University (Sweden); the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil); the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (Panama); Ulm University (Germany); and CREAF (Catalonia, Spain).

Gauci, V., Pangala, S.R., Shenkin, A. et al. Global atmospheric methane uptake by upland tree woody surfaces. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07592-w