Uforest’s first generation of urban foresters will transform a paved square of the UAB into a climate shelter

A 2000 m2 expanse of concrete wrapped around grassy patches and a handful of trees that survive between enormous university buildings: This is the Plaça del Coneixement (“Knowledge Square”), a large, public space in the grounds of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), and now part of an educational challenge in the European project Uforest.

In September, 20 students from Uforest’s partner universities – the UAB, the Polytechnic University of Milan (POLIMI), Trinity College Dublin (TCD) and Transilvania University of Brașov (UNITBV) – attended the project’s first urban forest specialization course to learn how to turn grey into green. Over two weeks, split between Barcelona and Milan, they worked on a challenge: designing an urban climate shelter based on reforesting this allegorical university square.

Through classes and field trips, the students found out about the local and global benefits of urban forests, as well as all the complications their creation and maintenance involve; water shortages, interactions between species, space limitations and economic interests are just a few of the difficulties to which an innovative approach is required to ensure a long-term positive impact. The specialization course enabled the students to develop a holistic perspective, for balancing the needs of nature and people in an anthropized environment.

Working in groups, the students came up with four competing proposals. Each proposal had to guarantee the ecosystem services of shade, heat mitigation, and relaxation;promote biodiversity; make reasonable use of water; and allow for the social use of the square. The titles of the four were Uniforest, El Bosc Glial (“The Glial Forest”), The Meandering Forest, and Diversity as an Urban Recipe.

According to Joan Pino, CREAF’s director and one of the course’s coordinators, the experience acted as a pilot test for a future Urban Forestry Lab (an innovative forum for the co-creation of urban forests), which would be aligned with the UAB Open Labs network, offer teaching, and involve CREAF and local authorities, such as AMB (the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona’s public administration body) and Barcelona City Council.

We have sown the seeds of an Urban Forestry Lab that would offer teaching and involve a research centre and local authorities.

Joan Pino, CREAF’s director and one of the course’s coordinators

The students: diversity, creativity, and the desire to change the world

The course’s students were strikingly diverse in their educational and cultural backgrounds. Their fields of study ranged from architecture, biology and forest engineering to finance and business management. Their interests included sciences, arts, languages and sports. What they had in common was “a desire to make the world a better place,” said Corina Basnou, a CREAF researcher participating in the Uforest project. “The experience was so rewarding that it rekindled my passion for teaching,” she added. Course co-coordinator Daniela Haverbeck remarked that the students were motivated by making a difference rather than by winning a prize. “There was a certain spirit of working for the same cause, which reflects the reality of urban forestry,” explained Joan Pino. “We showed the students that true value lies in cooperation, not competition. The walk on the first day was a baptism of fire; it encouraged them to step out of their comfort zone.”

The students shared a desire to make the world a better place. They were motivated by making a difference, not by winning a prize.

Daniela Haverbeck, course co-coordinator, and Corina Basnou, CREAF researcher

The students may not have had prior knowledge of urban forestry, but nature’s relationship with towns and cities had influenced their lives:from bat conservation in Pamplona and the serenity and beauty of the Japanese Garden of Toulouse, to opposition to a development project in Arenys de Mar and the natural disasters that have blighted the ancient city of Tenochtitlan due to excessive development following colonization. This is reflected in the following statements:

I am a climate activist and I want to devote my time to nature conservation. I think young people find urban forests particularly appealing.

Alaitz Meiyue Azcona, environmental biology student

I would like to work with urban forests to improve the lives of people who live in cities where there are great inequalities and few resources.

Belen Belda, environmental biology student

When I was younger, I saw photos of vertical gardens, of buildings that were covered with plants and had green roofs, and wondered why there were not more of them.

Júlia Alegre, environmental biology student

In Estonia, I saw how people lived in harmony with nature, which was an intrinsic part of their culture and identity. It was absolutely inspirational.

Maria Ibarz, environmental biology student

Urban development competes with the creation and expansion of urban forests, which could be seen as a threat to space.

Alexander Otto, environmental, economic and social sustainability student

Finance has a great influence on the destruction of nature. It is all a question of power. I want to help defend dignity, life and beauty.

Luis Torres-Farrell, environmental, economic and social sustainability student

The winning design: an agora of knowledge and an oasis

The four designs were of a very high standard, with little to choose between them in terms of quality and innovation. After evaluating them, the UAB’s Sustainability Office selected El Bosc Glial as the winning design, deeming it the most viable and most in line with the university’s campus naturalization strategy.

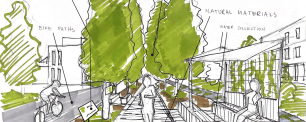

El Bosc Glial envisages the Plaça del Coneixement as a green corridor with an open-air library and an edible forest. It will have various water deposits and solar panels, as well as a bike path, trees to regulate the climate, and bushes, flowers and aromatic plants to encourage biodiversity and delight the senses. The brainchild of Bianka Łomnicka, Júlia Alegre, Juliana Voinescu, Laura Saison and Luis Torres, the design is inspired by glial cells, which support and protect neurons. It aims to establish a shelter for knowledge, biodiversity, and harmony with nature.

Two of El Bosc Glial’s designers will be giving a public presentation of the proposal on 5 December 2023. Would you like to attend?

To conclude, here are some spiritual reflections from Luis Torres and Júlia Alegre:

I come from Tenochtitlan, the Venice of Mexico, a city built on a lake. Its citizens lived in harmony with the natural environment 500 years ago. My grandfather told me that the canals ran to the centre of the city, and that people used to travel down them in traditional colourful boats called trajineras to sell their wares. The only indication of what the ancient city on the lake was like is Xochimilco; there are views of the volcanoes, and the canal system has been preserved for agriculture.

Nowadays, the ecosystem is very different. Colonization led to the lake being drained for urban development. As a result, the ground is unstable and we suffer natural disasters, such as earthquakes and floods, which cause deaths. That is what happens when you go against nature’s design.

On the other hand, the earthquakes and floods that have destroyed colonial buildings have revealed archaeological remains, such as ancient pyramids below churches. . It is as if the city underneath were breaking through the city above! Could this be the revenge of Tláloc, the rain god?

Luis Torres-Farrell, environmental, economic and social sustainability student

I believe nature is something we experience spiritually. It is somewhere we go to find calm and escape the hustle and bustle of the city; a place we visit, specifically and deliberately, in search of the peace inherent in green areas. As a result, we end up regarding nature as a mere service, rather than as a complex, functioning, living body. Nature thus becomes a distant concept, one that is practically cultural, inert, and external to the rhythms of metropolitan life. It could even be said to be a commodity for those able to allow themselves the luxury of visiting it.

As far as city dwellers are concerned, changes in season mean nothing more than changes in temperature. At most, they notice the Platanus x hispànica leaves in autumn and realize that the chestnut season has arrived. Their lives are disconnected from true nature and its cycles.

So, I see urban forests as a way to reconnect nature and people. . I imagine a space where everything is green and calm, where recreation is secondary, and plants take centre stage.

Júlia Alegre, environmental biology student