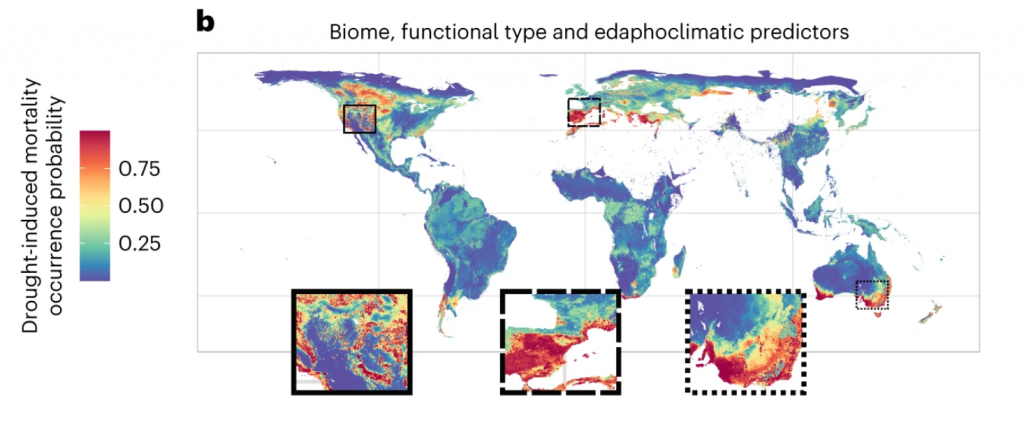

The forests at the greatest risk of drought-induced death are in the Mediterranean basin, southern Australia, western North America, and western tropical South America

Mortality is rising in forests around the world because of the increasing frequency and severity of droughts. Led by CREAF researcher Pablo Sánchez-Martínez, a study just published in the renowned journal Nature Ecology and Evolution presents world maps that show which forests run the greatest risk of dying because of a lack of water. The most vulnerable, according to the study’s predictive model, are those of the Mediterranean basin, southern Australia, western North America, and western tropical South America. To produce the maps, Sánchez-Martínez and his team established a new method that combines physiological data on the strategies thousands of species use to cope with water scarcity, evolutionary and phylogenetic data on adaptation to drought, and data on soil and climate conditions in each of the planet’s biomes. The new method’s main innovation consists in assessing a forest as an entire ecosystem, a range of organisms that respond differently to external conditions; this paves the way for much larger-scale predictions of how climate change will affect Earth’s forests.

“Physiological data on individual species tell us that many Mediterranean trees are well suited to dealing with drought. Nonetheless, our model shows Mediterranean forests to be at a very high risk of drought-induced mortality. That is because our method enables us to zoom out and see that the region is also home to species that are very sensitive to drought, and that drought episodes here are becoming longer and longer, and more and more frequent.”

PABLO SÁNCHEZ-MARTÍNEZ, investigador del CREAF i autor principal d’aquest estudi que forma part de la seva tesis doctoral.

The CREAF-based ICREA researcher Maurizio Mencuccini also participated in the study, as did the Autonomous University of Barcelona lecturer and CREAF researcher Jordi Martínez-Vilalta.

Camel-like trees

Some trees have a high safety margin and can withstand a lack of water because, like camels, they store it and need only a small amount to stay alive.

In general, when a tree dies due to extreme drought, it is because it is impossible for water to circulate properly in its trunk, a consequence of its transport vessels (a tissue called xylem) weakening or becoming clogged. The process in question is known as hydraulic failure. Science is aware of physiological parameters that indicate how well a species is protected against such failure. One of the most notable is thehydraulic safety margin,i.e. the margin between the amount of water a tree can mobilize during a drought episode and the minimum amount of water it needs to survive. Some trees have a high safety margin and can withstand a lack of water because, like camels, they store it and need only a small amount to stay alive. Others, however, are less able to cope with such conditions and are thus extremely vulnerable to drought. Having data on the parameter in question for all the world’s plant species would allow us to make accurate predictions; unfortunately, we have such data for just 1.5% of them.

So, while vital to understanding which forests are most likely to be affected by hydraulic failures and drought-induced mortality, physiological data of the kind described above are limited. Incorporated into the new model used in the study, however, they provide information that is highly useful on a much more general level. “Our study presents the first global characterization of forest mortality risk, but there is still a great deal of work to be done: the predictions set out in the article are a first step, and will need to be complemented and improved in the near future,” concludes Sánchez-Martínez.

Referenced article

Sanchez-Martinez, P., Mencuccini, M., García-Valdés, R. et al. Increased hydraulic risk in assemblages of woody plant species predicts spatial patterns of drought-induced mortality. Nat Ecol Evol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02180-z.